This is the first in a series of articles that will explore the status of Boulder’s Climate Action Plan and our performance in trying to meet the Kyoto Protocol. Over the coming weeks, we will attempt to understand the major contributors to our greenhouse gas (GHG) footprint, how the figures for the contributing sectors are calculated, the basis for the City’s recommended remedies, and what actions would have the most impact. We intend this series of articles to be a personal guide to

- understanding Boulder’s climate actions

- making personal choices to reduce your own carbon footprint, and

- focusing on areas where citizen advocacy could help move us in the right direction.

The Kyoto Goal

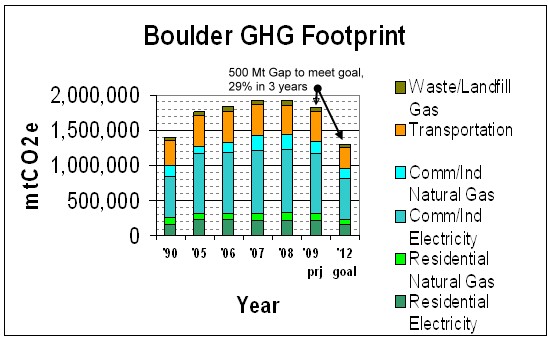

Let’s start with the basics. The goal, as set by the Kyoto Protocol, is to reduce Boulder’s GHG footprint to a point that is 7% less than our GHG footprint was in 1990. Greenhouse gases (a combination of carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases) are generally measured and/or calculated in metric tons CO2 equivalent (mtCO2e). For ease of communication and understanding, we will generally round our figures off to the nearest 100,000 (or 100K) metric tons (mt) in these articles.

In 1990, Boulder’s GHG footprint was about 1400K metric tons. Thus our Kyoto goal is about 1300K mt (7% less than the 1990 level). As a City, we made the commitment to meet the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. In 2005, our calculated GHG footprint was about 1750K mt. The Climate Action Plan (CAP) was developed shortly thereafter to provide a framework for addressing local greenhouse gas emissions. The Plan was financed in part by the CAP tax, the nation’s first “carbon tax.”

In 2006 and 2007, our GHG footprint continued to grow by about 100K metric tons per year. In 2008 that trend began to reverse, dropping a few metric ton equivalents to about 1900K mt. Primary contributors to the reduction in 2008 were the increased purchase of WindSource renewable energy credits from Xcel (a program that reduces the impact of residential electricity use by encouraging Xcel’s purchase of electricity from wind farms) and decreased driving due to the high gasoline prices experienced in 2008.

2009 figures are not yet available, but Boulder’s GHG for last year is expected to drop by about 100K mt based on City projections, primarily attributed to the impact of Colorado’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) which reduced the projection for 2009 emissions attributed to electricity use due to the increased use of renewable energy in the energy mix state-wide.`

That means we have about 500,000 metric tons of ugly GHG “fat” to lose to meet our goal over the next 2 years. That’s almost a 30% reduction from current our current GHG emissions –an Oprah-sized GHG diet is in order.

The Numbers

So, where do these numbers come from, anyway? The “science” of estimating greenhouse gases is far from exact, primarily due to vagaries in the definitions of how gases get allocated. For instance, do the greenhouse gases generated by the Valmont coal-fired plant get added in, or is it included in the footprint of the sum of all electricity used in the City? If someone commutes into Boulder, how much of their emissions gets “credited” to us? Consistency in the way we calculate the GHG footprint from year to year and from city to city is an important factor in achieving our goal.

Starting in 2004, Boulder’s greenhouse gas footprint was calculated by WSP Environment and Energy (WSP E&E, formerly Econergy) using standard methodologies provided by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) of the UnitedNations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The Inventory is based on accepted international protocols in keeping with a similar approach that other cities with climate change objectives have used. In 2008, Boulder emissions were calculated by City staff and other third party consultants engaged by the city.

The primary basis for the GHG inventory is the historical consumption of electricity and natural gas, disaggregated by sector. The necessary historical energy consumption data are acquired from City of Boulder, University of Colorado Boulder, and Xcel Energy. For the most part, annual data for the consumption of electricity and natural gas are available from 1990 through 2007. According to WSP E&E, the completeness of the data set puts the City of Boulder in a good position to make informed decisions regarding the design of programs and policies that aim to manage the city’s GHG future. Transportation emissions are estimated with a data set obtained from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE).

The inventory does not cover emission sources considered to be insignificant and/or not readily controlled by local government actions. These excluded emission sources include aviation and locomotive transportation, agricultural enteric and manure sources, solvent use, land use and forestry, and industrial process emissions not associated with energy usage. Finally the inventory does not include the emissions related to the production of most goods bought or consumed in the city.

The Main GHG Culprits

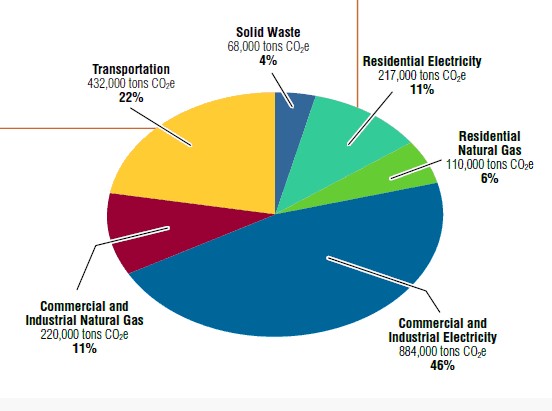

According to the Community Guide to Boulder’s Climate Action Plan , the primary sources of greenhouse gases in our city in 2007 were:

While the residential and transportation sectors have remained relatively constant, Boulder’s current average population growth of 500 people per year adds about 70Kmt in GHG each year. The commercial/industrial sector has also shown significant historical growth, and consumes a much greater percentage of its energy as electricity than the other sectors.

The Guide indicates that we can meet our Kyoto goals with the addition of funds made available by last year’s City Council decision to maximize the CAP tax. The primary source of projected reductions (65% of projections) would be about 270K mt from reduced use of energy, about equally split between residential and commercial/industrial sectors. Given that Commercial and Industrial sources contribute well over three times the GHG to our footprint than the Residential sector, we will explore in future articles why the reductions for each sector are relatively equal.

The second biggest source of reduction is projected due to increased use of energy from renewable resources. Work at the regional and state level, combined with local incentives for solar installations would reduce these GHG emissions by about 90K mt, about 21% of projected reductions. The remaining projected reductions would come from changes in transportation, building practices, and waste reduction.

Future articles will explore the assumptions behind the main sources of these savings, including the implications of Boulder’s SmartGrid, the Colorado Clean Air Standard, and the addition of more renewable energy to our mix.

We are looking forward to sharing more about how the GHG numbers are calculated, where the funds raised by the CAP tax are being spent, and what actions in the various sectors are most critical to meeting our 2012 goal.