Editor’s note: PLAN-Boulder County has issued a report entitled Does Dense Make Sense? This is the fourth part in a six part series extracted from the report.

The Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan has a policy stating that all new development will “pay its own way.” This means that current levels of public services should be maintained as new development occurs. Policy 3.05 states, “Growth will be expected to pay its own way, with the requirement that new development pay the cost of providing needed facilities and an equitable share of services including affordable housing, and to mitigate negative impacts such as those to the transportation system.”

These goals are laudable and establish a legal justification for assessment of development fees on all new residential and commercial development. These fees should be set so that we maintain adequate public facilities and do not degrade levels of service. Unfortunately, the current level of impact fees and development excise taxes are inadequate to achieve these policy goals in almost all areas of city-provided services. For example, recent empirical evidence shows that some public services such as libraries and fire stations are overburdened while nearby housing is built without any financial contribution to these services. The City’s own studies show that transportation funding is inadequate to prevent massive increases in congestion. The Blue Ribbon Commission I identified building maintenance and replacement, and replacement of fire apparatus, as critical budget deficiencies.

New development also has ongoing impacts beyond facilities construction. Witness the current debate over paving of subdivision roads in the county. This year’s draft Capital Improvement Program (City of Boulder) states in the Introduction that, “While dedication of certain funding streams by voters has provided funds for some capital needs, it has not provided ongoing new monies to pay for new operational costs. In some situations sufficient capital funds have been accumulated to build the project, but lack of operating dollars have put the project on hold . . .”

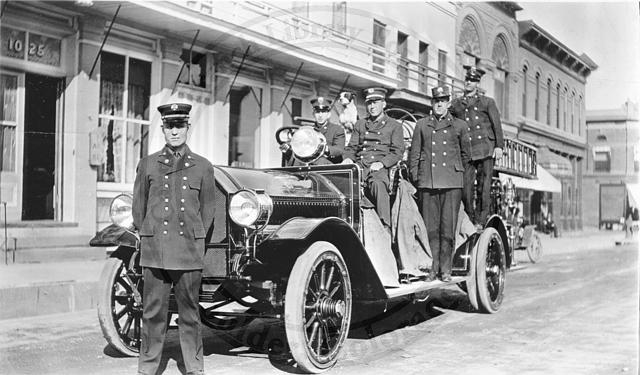

Emergency Services

The Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan sets service standards for response times for emergency services. Per the BVCP, when one fire response unit in a station exceeds 1,500 calls per year, additional fire engines and staff must be provided. Three of Boulder’s seven fire stations currently exceed this service standard: Station 1 is downtown, Station 2 is at Broadway and Baseline, and Station 3 is at 30th and Arapahoe. In 2007, Station 1 received 2,402, Station 2 received 1,892 calls and Station 3 received 2,274 calls.

Last year, Boulder’s firefighters met their goals of arriving at the scene within 6 minutes only 65% of the time. In 2007, they met the standards 80% of the time. This service gap has been widening steadily for the last few years according to an article in the Colorado Daily, February 10, 2010. Fire department staff have testified that more density creates more calls. Routine delivery is more difficult in dense areas due to congestion and the configuration of Boulder’s streets (lots of collector streets, few arterial streets). All of these factors combine to reduce response time.

Station 3 will be directly impacted by the area formerly known as the Transit Village and, depending on the outcome of the Streets and Centers project, Station 2 could see some impact. Since these two fire stations have exceeded the service level spelled out in the BVCP, any additional growth in these areas will need to finance additional services. It is unclear if the City has identified any impact fees to these service areas to raise additional revenue for emergency services. One-time development fees may not pay for the additional growth because the cost to operate the stations is an ongoing expense.

Libraries

Libraries are important public services that are needed in each community to “enhance the personal and professional growth of Boulder residents and contribute to the development and sustainability of an engaged community through free access to ideas, information, cultural experiences and educational opportunities.” Unfortunately, current library funding sources only include operational funds, not capital funds for new facilities. According to the Boulder Public Library (BPL) 2007 Master Plan, BPL’s service delivery model proposes the development of a branch library when the population in a geographic quadrant of Boulder reaches 10,000 – 15,000 residents, a service area size that provides the usage needed to justify the costs.

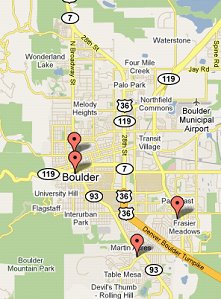

Looking at a map of the City of Boulder, it is clear that the areas intended to accommodate most of the new growth have no library facilities near them. The Transit Village and the Holiday neighborhood on North Broadway are intended to be walkable, complete communities where much of the new growth would occur. In the case of the Holiday neighborhood, construction of a North Boulder branch was recommended as part of the 1995 Library Master Plan and the North Boulder Subcommunity Plan. The developer dedicated a parcel of land but there have never been sufficient funds to build or operate the new facility despite requests for one in BPL user surveys.

Though the library size has not been determined, an 8,000 square foot branch would cost $350,000-400,000 per year to operate. This amounts to an 8% increase in the BPL operating budget. Partial funding of $1.5 million has been allocated to construction of the facility through the Capital Development fund but it is not appropriated. It is now estimated that an additional $2.6 million will be needed to build the branch.

Most of Colorado is served and funded by Library Districts. In Boulder, raising money for additional operations requires a property tax increase, which begs the question, “Why would South Boulder residents vote to tax themselves to build a library branch in North Boulder?” Today, the library’s operating budget is heavily dependent on the City’s general fund. Only 11% of BPL operations are supported by the Library Fund, which includes monies from the mill levy increment (9%), fines and fees, gifts, and miscellaneous revenue sources (2%). This heavy reliance on the general fund has resulted in significant program and service reductions during recent periods of budget cuts. To accomplish the vision of functional, walkable communities, and to avoid overburdening existing library facilities, the City should ensure that new developments are contributing their fair share to new capital facilities. It is critical that impact fees charged to new development are adequate to develop new library facilities.

Parks and Recreation, Greenways, and Open Space

Surveys of Boulder residents have repeatedly found that recreational opportunities, open space, and the greenways and bike path systems are among the most important aspects of Boulder for its citizens. The departments providing these important services are stretched thin by the current budget crisis, and increasing housing density could be expected to exacerbate their difficulties.

Greenways System

The Greenways system consists of a series of riparian corridors along Boulder Creek and six of its tributaries, jointly administered by the Parks and Recreation, Open Space and Mountain Parks, and the Transportation Departments, with input from various advisory boards. Bike paths are the responsibility of the Transportation Department.

Parks and Recreation Department

The Parks and Recreation department operates more than 60 city parks, 3 recreation centers, Boulder Reservoir, 22 ballfields, 48 tennis courts, 3 outdoor swimming pools, and a number of other facilities. These are all heavily used by Boulder’s active population, and redevelopment projects that are denser than current housing will increase the demand for all these recreation and park facilities.

Under the budgetary pressures of the recession, maintenance and operations have been cut back, and closing the South Boulder Recreation Center has been discussed. The Parks and Recreation Department is dependent on the general fund for most of its budget, with some contributions from user fees and from state lottery funds. It also receives some capital improvement funds from a dedicated sales tax.

Open Space and Mountain Parks Department (OSMP)

Boulder was the first municipality in the United States to tax itself for the purchase of open space. The campaign to pass this measure followed passage of the Blue Line, which prohibited supplying city water above a certain elevation; the movement was citizen led and initiated, and it was closely tied to the founding of PLAN-Boulder. Open Space was made a part of the City Charter, which provides:

Open Space land shall be acquired, maintained, preserved, retained, and used only for the following purposes:

- Preservation or restoration of natural areas characterized by or including terrain, geologic formations, flora, or fauna that is unusual, spectacular, historically important, scientifically valuable, or unique, or that represent outstanding or rare examples of native species;

- Preservation of water resources in their natural or traditional state, scenic areas or vistas, wildlife habitats, or fragile ecosystems;

- Preservation of land for passive recreation use, such as hiking, photography or nature studies, and if specifically designated, bicycling, horseback riding, or fishing;

- Preservation of agricultural uses and land suitable for agricultural production;

- Utilization of land for shaping the development of the city, limiting urban sprawl and disciplining growth;

- Utilization of non-urban land for spatial definition of urban areas;

- Utilization of land to prevent encroachment on floodplains; and

- Preservation of land for its aesthetic or passive recreational value and its contribution to the quality of life of the community.

Over 45,000 acres of land is administered by OSMP, some of it purchased outright, and some protected by some type of conservation easement. Open Space provides 144 miles of trails, and Boulder’s citizens have increasingly viewed recreational uses of open space as a critical purpose of the system (2004 Attitudinal Survey).

OSMP is funded 90% by dedicated sales taxes (Financial Overview, 2008). A 0.40% tax was passed in 1967 by a 61% margin, and several additional dedicated sales tax increments have been passed, mainly for acquisitions. The incremental sales tax increases are generally scheduled to expire in conjunction with completion of the Open Space Acquisition Plan, which has less than 7,000 acres remaining as targets for acquisition.

In terms of meeting the needs of a denser city, open space acquisitions, particularly of lands suitable for recreational use, are nearing an end. Boulder will have to live with the open space it has already purchased. The remaining 0.40% sales tax will be dedicated to managing the land acquired in the past.

OSMP receives some funds from the Colorado lottery, for which it competes with the Parks and Recreation Department. As a result of the merger of the Mountain Parks in 2001, some funds are supposed to be transferred from the general fund to cover maintenance of the trails that were formerly in the Parks Department budget, but this commitment has never been fully funded, and the recent budget crisis has reduced it further.

Increasing Demands and Pressures

Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks lands are known and loved far beyond the population of the city. They are a destination of choice for users from throughout Boulder County, the Denver metropolitan area, and many other places. The result is a flood of visitors whose objective is to climb, hike, bird watch, mountain bike, or walk their dogs on OSMP lands. Visitation had reached nearly 5 million visitor days a year in 2004-05 (Vaske et al., 2009). Measurements are not strictly comparable, but this is a visitor load larger than that of Rocky Mountain or Yosemite National Parks, concentrated in a much smaller area, with far fewer trail miles. Obviously, these visitors are not all Boulder residents, and anecdotal reports suggest that at the southern trailheads, more and more users come from the Denver metropolitan area outside Boulder County. At major trailheads six or seven years ago, however, 81% of users said they were from Boulder County (Vaske and Donnelly, 2008).

This heavy use creates an enormous challenge, both for funding and for management that is charged with preserving the natural systems in perpetuity (1968 City Council Resolution #24).

Whenever these issues are discussed, suggestions are made that the City should recoup some of the costs of maintaining open space from out-of-town visitors, particularly those not contributing to sales taxes through Boulder businesses. Since there are currently at least 236 publicly accessible, widely dispersed access points to OSMP lands (Vaske et al., 2009), this would not be feasible without major changes to accessibility. Expenses for collection and enforcement also present major obstacles.

Finally, in addition to the increasing view among Boulder residents that recreational use of open space is its most important purpose, there are increasing demands to accommodate new activities, such as mountain biking, on open space lands, which may conflict with current uses.

Summary

The unique open space preserved by the citizens of Boulder over the years has long been one of the major attractions of Boulder and a source of pride in the community.

The challenges of preserving the quality both of ecosystems on OSMP lands and the quality of the visitor experience is difficult for many reasons, and these challenges will become more acute with the growth in population throughout the metropolitan area, not just in Boulder or Boulder County. The demand for experience of a natural environment close to the city will grow with population pressures, environmental change, and growth of the student population at the University of Colorado.

The challenges can only be exacerbated by increased density in the City of Boulder. More dense housing means that the opportunity to get outside increasingly can only be satisfied by using public spaces, which increases pressures on both city parks and on open space lands.

Since it is difficult to add new city parks while increasing population density, and very little new open space can be added to the City of Boulder, these are services where growth really cannot pay its own way. Increased population density will entail degradation of these services and of the quality of life for Boulder residents. Eventually, some measures to limit usage will have to be implemented.

Education

Recent budget shortfalls in the Boulder Valley School District (BVSD) have brought attention to the issue of funding in local schools. State law forbids school districts, cities, and counties from imposing school impact fees on new development. Although the City of Boulder once had an Education Excise Tax that was intended to substitute for such impact fees, the tax was recently suspended because it was not achieving its planned purpose. In absence of a funding source, we can expect BVSD to put a bond issue on the ballot to pay for new facilities in the future, especially in East Boulder County where much of the residential growth is expected to take place. This places the funding burden on existing property owners rather than the new development.

Water

The 2002 drought was a shock to many Boulder residents who had become used to unlimited supplies of water for irrigation and indoor use. Unlike other Front Range cities that regularly impose watering restrictions, Boulder seemed to always have adequate supply. Were the 2002 watering restrictions a consequence of growth or a meteorological fluke? The answer is probably “both.”

During 2002, supplies were extremely low (1 in 300 year streamflows), and the summer particularly dry. Landscaping suffered and some trees were lost. In August of that year, under community pressure, the City modified the watering restrictions to allow limited, deep watering of trees.

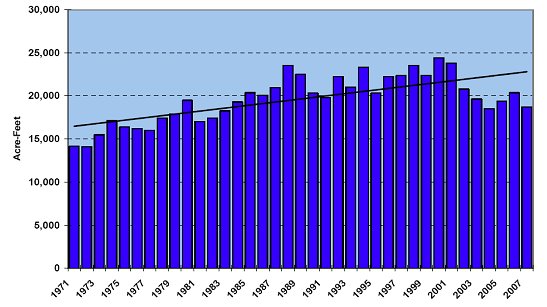

With watering restrictions, Boulder was able to deliver 20,770 acre-feet of water to its service area customers in 2002. If the drought had happened in the 1980’s, instead of the 2000’s, full delivery might have been possible. Demand for water fluctuates, and there was a significant decrease immediately after the 2002 drought, but in general, with increasing population, Boulder’s water use has been increasing. Water demands are projected to reach 24,159 acre-feet by 2020.

Figure 6. Boulder’s Total Treated Water Use, 1971-2007

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, Volume 2, 2009

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, Volume 2, 2009

Supplies

From a water supply perspective, Boulder is in much better shape than many Front Range cities. First, Boulder’s water rights portfolio contains very senior rights, meaning that shortages will be imposed on more junior rights before Boulder feels the pinch. For example, according to the Source Water Master Plan, 2009, “even in 2002, when natural flows were less than 50 percent of average, Boulder’s direct flow rights yielded 88 percent of their average.” These water rights provide about 70% of Boulder’s treated water supply. Second, Boulder has redundancy built into its system — it receives water from two different basins: the Boulder Creek basin and the Colorado River basin via the Colorado-Big Thompson (CBT) project. The CBT project provides about 30% of Boulder’s treated water supply.* In contrast, the City of Aurora receives nearly all of its surface water via the South Platte River at a single diversion point. Boulder also has significant storage facilities for a city of its size.

What are the vulnerabilities in Boulder’s water supply system? Of obvious concern is climate change. The City, in cooperation with a number of consultants and scientists, conducted a study for NOAA of the impacts of climate change on the City’s ability to meet its projected water demands at “buildout.” That study found that, under worst case scenarios with full buildout demands, the “potential for violating drought criteria rise[s]” (Smith, et al., 2009).

Another vulnerability hinges on Boulder’s dependence on west slope water. The west slope is in the Colorado River basin and as such is subject to the Colorado River Compact. In the future, increasing demands for water in Lower Basin states (New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California) combined with long term drought could compel one or more Lower Basin states to invoke a “Compact Call” forcing many Upper Basin (Utah, Wyoming and Colorado) water users to bypass water that would normally be stored or diverted. Since a significant portion of Boulder’s water supply comes from the Colorado River basin, a Compact Call could have a large, negative impact.

Finally, Boulder’s population density actually reduces its drought response flexibility. Under drought conditions in most communities, cutting back outdoor water use is usually sufficient and indoor uses are protected. However, unlike most Front Range cities, Boulder’s water use is about 2/3 indoor and 1/3 outdoor. In other cities the ratio is reversed. Since the majority of Boulder’s water use is already indoor use, watering restrictions, as a drought response tool, are less powerful.

Perhaps not in the category of vulnerability, but annexation and development of rural properties by the City will require replacement of ditch irrigation (or no irrigation) with treated water for whatever uses are allowed, placing an additional burden on both capacity and supply.

Funding

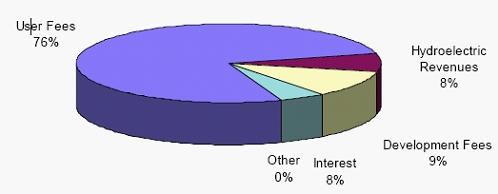

Unlike our use of libraries and emergency services, we pay directly, every month, for our water use, and the rate we pay has some relation to the amount of water we use and the cost to provide that water. The City of Boulder provides water, sewer and stormwater services through the Utilities Division of the Public Works Department. To pay for these services the City assesses both user fees (water rates) and development fees. The bulk (76%) of the City’s water utility funding comes from user fees, with development fees being the next largest source of funding at 9%.

Figure 7. Water Utility Funding Sources

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, April 2009, Volume 1The revenues from water rates are used to pay for daily operations and maintenance and for repair and replacement of aging facilities. Development fees are used to pay for increasing facility capacities in the system. Water Plant Investment Fees (PIF) start at $9,282 for a new single family home and increase with irrigated area on the lot. The wastewater PIF for a new single family home is $3,356 and the stormwater PIF is $1.37 per square foot of impervious area. Development fees are being used to pay for recent pipeline and treatment capacity expansions. Further capacity expansions to meet future demands are not expected.

Following the drought of 2002, per capita water use dropped about 20%. Long-term behavior and fixture (toilets, shower heads) changes may have set in. This reduction in water demand is resulting in reduced revenues to the water utility, which has primarily fixed costs. However, studies have shown that water use is higher in higher income households. According to the City’s Source Water Master Plan, “If the average income in Boulder continues to increase, it may also affect residential water users’ habits and preferences, although it is difficult to predict in what way. Installation of backyard fountains and water features often occurs at higher income levels. Water intensive indoor plumbing features, such as soaking tubs and rain showerheads, are often favored in more expensive homes.”

Summary

Because of aggressive and visionary water acquisition efforts since Boulder’s founding, Boulder is in a relatively good water supply position. Development impact fees have paid to increase capacity and users are billed for water delivery. However, growth cannot produce more precipitation. With or without climate change, as the population increases, and water demand grows, Boulder can expect more periods of watering restrictions, more periods of depleted streamflows, more impacts to aquatic and riparian ecosystems, and fewer stream-based recreational opportunities.

Transportation

The City of Boulder has a Transportation Master Plan that identifies expected transportation levels of services and funding sources to pay for improvements. Close analysis of the TMP, however, reveals that current funding structures do not begin to approach the amount needed to maintain the level of services. The City’s web site states that transportation congestion and delays escalate massively, even at maximum levels of proposed funding. As indicated in the City’s own materials, the current version of the TMP would have Boulder become hugely congested, even if the City had the hundreds of millions of dollars that the TMP budget is projected to be short.

The City staff’s current proposal to tax all property owners to pay for the costs of needed transportation facilities is not only inequitable, but is inefficient, as it provides no incentive to actually reduce driving as a parking charge would. A more equitable source of funding would be development impact fees and excise taxes to deal with the impacts of growth, and parking charges to handle increased operation and maintenance costs. Unfortunately, the Transportation Excise Tax — despite recent increases — is still inadequate to deal with the impacts of additional traffic caused by new development. In addition, the TMP fails to adequately manage the demand for transportation as it avoids strategies that directly reduce driving such as expanding managed parking in employment areas in East Boulder or requiring new developments to offset their vehicle trips.

Because Boulder is committed to alternative modes rather than expanding the street network, impact fees are not a solution, as by state law they can only be used for capital facilities. Alternative modes are operating cost intensive. The solution is to use the Fort Collins “adequate public facilities” approach as a legal basis and apply it to the City of Boulder’s goal. New development would be required to prevent the deterioration of levels of service by offsetting its additional trips, which could be done by having new developments paying existing developments to car pool or van pool or by subsidizing delivery services, and so on.

Does Adding More People Help?

Many municipalities add more housing and commercial development with the intention of generating tax revenues and/or impact and development fees. Since the City of Boulder does not collect sufficient development fees to fully maintain its per capita level of service, adding population under the current impact fee system will result in lowered levels of service to existing residents for everything from water to emergency services. Further, although historically Boulder residents and businesses have benefited from tax revenues from regional shopping, adding more residents will dilute this revenue pool on a per capita basis, resulting in even lower levels of city services.

There is widespread belief that if development fees were increased, the housing stock in Boulder would become more expensive, further exacerbating the affordable housing issue. It is likely that initially an increase in development charges would impose a burden on individuals who bought property contingent on previous low levels of these fees. In turn, a sharp increase in fees would be a hardship on the developers who bought property counting on not having growth being required to pay its own way.

If new development fees were phased in over time, however, the increases in development fees would not increase the final sales prices and thus not adversely affect these developers. In fact, these fees would just push the price of developable land down. This is because regional markets set the final sales prices of new homes. The final sales price is composed of the cost of land value and the cost to develop that land. If the cost to develop the land were to increase, the value of the land would decrease. Thus, over time increased development fees are less likely to fall on the purchasers (i.e. new residents looking to buy a home in Boulder) but rather will fall on the real estate speculators. One interesting analysis (Pomerance) shows that if the full costs of growth were charged, green field land would sell for not much over its agricultural value, which would allow local agriculture to be preserved.

Summary

The municipalities within Boulder County should pass impact fees, excise taxes and/or Adequate Public Facilities ordinances that take into account all of the real impacts of growth. Impact fees should be set at the full cost of adding capital facilities sufficient to maintain levels of service. Adequate Public Facilities ordinances should also set levels of service standards. When a new development is proposed, the municipality would evaluate the impacts on all services and if any are pushed below the standard, the proposed development would be required to invest an amount adequate to bring the level of service back up to standard, or the development permit would be denied. This approach is especially valuable in transportation where the solution to a potential increase in traffic may be an investment in an operating-cost intensive approach like transit rather than a capital-cost intensive approach like adding turn lanes.

Applying the goals of the BVCP to all of Boulder County could create a template for sustainable growth in the county. Unfortunately, the current level of impact fees and development excise taxes are inadequate to achieve these policy goals.

Stay tuned for Part 5: Affordable Housing

Note

* Additional CBT water is released to Boulder Creek below Boulder to allow the City to take advantage of exchange opportunities and divert additional Boulder Creek flows upstream. When this use is included, CBT water makes up about 50% of Boulder’s supply.

he Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan has a policy stating that all new development will “pay its own way.” This means that current levels of public services should be maintained as new development occurs. Policy 3.05 states, “Growth will be expected to pay its own way, with the requirement that new development pay the cost of providing needed facilities and an equitable share of services including affordable housing, and to mitigate negative impacts such as those to the transportation system.”

These goals are laudable and establish a legal justification for assessment of development fees on all new residential and commercial development. These fees should be set so that we maintain adequate public facilities and do not degrade levels of service. Unfortunately, the current level of impact fees and development excise taxes are inadequate to achieve these policy goals in almost all areas of city-provided services. For example, recent empirical evidence shows that some public services such as libraries and fire stations are overburdened while nearby housing is built without any financial contribution to these services. The City’s own studies show that transportation funding is inadequate to prevent massive increases in congestion. The Blue Ribbon Commission I identified building maintenance and replacement, and replacement of fire apparatus, as critical budget deficiencies.

New development also has ongoing impacts beyond facilities construction. Witness the current debate over paving of subdivision roads in the county. This year’s draft Capital Improvement Program (City of Boulder) states in the Introduction that, “While dedication of certain funding streams by voters has provided funds for some capital needs, it has not provided ongoing new monies to pay for new operational costs. In some situations sufficient capital funds have been accumulated to build the project, but lack of operating dollars have put the project on hold . . .”

The Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan sets service standards for response times for emergency services. Per the BVCP, when one fire response unit in a station exceeds 1,500 calls per year, additional fire engines and staff must be provided. Three of Boulder’s seven fire stations currently exceed this service standard: Station 1 is downtown, Station 2 is at Broadway and Baseline, and Station 3 is at 30th and Arapahoe. In 2007, Station 1 received 2,402, Station 2 received 1,892 calls and Station 3 received 2,274 calls.

Last year, Boulder’s firefighters met their goals of arriving at the scene within 6 minutes only 65% of the time. In 2007, they met the standards 80% of the time. This service gap has been widening steadily for the last few years according to an article in the Colorado Daily, February 10, 2010. Fire department staff have testified that more density creates more calls. Routine delivery is more difficult in dense areas due to congestion and the configuration of Boulder’s streets (lots of collector streets, few arterial streets). All of these factors combine to reduce response time.

Station 3 will be directly impacted by the area formerly known as the Transit Village and, depending on the outcome of the Streets and Centers project, Station 2 could see some impact. Since these two fire stations have exceeded the service level spelled out in the BVCP, any additional growth in these areas will need to finance additional services. It is unclear if the City has identified any impact fees to these service areas to raise additional revenue for emergency services. One-time development fees may not pay for the additional growth because the cost to operate the stations is an ongoing expense.

Libraries are important public services that are needed in each community to “enhance the personal and professional growth of Boulder residents and contribute to the development and sustainability of an engaged community through free access to ideas, information, cultural experiences and educational opportunities.” Unfortunately, current library funding sources only include operational funds, not capital funds for new facilities. According to the Boulder Public Library (BPL) 2007 Master Plan, BPL’s service delivery model proposes the development of a branch library when the population in a geographic quadrant of Boulder reaches 10,000 – 15,000 residents, a service area size that provides the usage needed to justify the costs.

Looking at a map of the City of Boulder, it is clear that the areas intended to accommodate most of the new growth have no library facilities near them. The Transit Village and the Holiday neighborhood on North Broadway are intended to be walkable, complete communities where much of the new growth would occur. In the case of the Holiday neighborhood, construction of a North Boulder branch was recommended as part of the 1995 Library Master Plan and the North Boulder Subcommunity Plan. The developer dedicated a parcel of land but there have never been sufficient funds to build or operate the new facility despite requests for one in BPL user surveys.

Looking at a map of the City of Boulder, it is clear that the areas intended to accommodate most of the new growth have no library facilities near them. The Transit Village and the Holiday neighborhood on North Broadway are intended to be walkable, complete communities where much of the new growth would occur. In the case of the Holiday neighborhood, construction of a North Boulder branch was recommended as part of the 1995 Library Master Plan and the North Boulder Subcommunity Plan. The developer dedicated a parcel of land but there have never been sufficient funds to build or operate the new facility despite requests for one in BPL user surveys.

Though the library size has not been determined, an 8,000 square foot branch would cost $350,000-400,000 per year to operate. This amounts to an 8% increase in the BPL operating budget. Partial funding of $1.5 million has been allocated to construction of the facility through the Capital Development fund but it is not appropriated. It is now estimated that an additional $2.6 million will be needed to build the branch.

Most of Colorado is served and funded by Library Districts. In Boulder, raising money for additional operations requires a property tax increase, which begs the question, “Why would South Boulder residents vote to tax themselves to build a library branch in North Boulder?” Today, the library’s operating budget is heavily dependent on the City’s general fund. Only 11% of BPL operations are supported by the Library Fund, which includes monies from the mill levy increment (9%), fines and fees, gifts, and miscellaneous revenue sources (2%). This heavy reliance on the general fund has resulted in significant program and service reductions during recent periods of budget cuts. To accomplish the vision of functional, walkable communities, and to avoid overburdening existing library facilities, the City should ensure that new developments are contributing their fair share to new capital facilities. It is critical that impact fees charged to new development are adequate to develop new library facilities.

Parks and Recreation, Greenways, and Open Space

Surveys of Boulder residents have repeatedly found that recreational opportunities, open space, and the greenways and bike path systems are among the most important aspects of Boulder for its citizens. The departments providing these important services are stretched thin by the current budget crisis, and increasing housing density could be expected to exacerbate their difficulties.

Greenways System

The Greenways system consists of a series of riparian corridors along Boulder Creek and six of its tributaries, jointly administered by the Parks and Recreation, Open Space and Mountain Parks, and the Transportation Departments, with input from various advisory boards. Bike paths are the responsibility of the Transportation Department.

Parks and Recreation Department

The Parks and Recreation department operates more than 60 city parks, 3 recreation centers, Boulder Reservoir, 22 ballfields, 48 tennis courts, 3 outdoor swimming pools, and a number of other facilities. These are all heavily used by Boulder’s active population, and redevelopment projects that are denser than current housing will increase the demand for all these recreation and park facilities.

Under the budgetary pressures of the recession, maintenance and operations have been cut back, and closing the South Boulder Recreation Center has been discussed. The Parks and Recreation Department is dependent on the general fund for most of its budget, with some contributions from user fees and from state lottery funds. It also receives some capital improvement funds from a dedicated sales tax.

Open Space and Mountain Parks Department (OSMP)

Boulder was the first municipality in the United States to tax itself for the purchase of open space. The campaign to pass this measure followed passage of the Blue Line, which prohibited supplying city water above a certain elevation; the movement was citizen led and initiated, and it was closely tied to the founding of PLAN-Boulder. Open Space was made a part of the City Charter, which provides:

Open Space land shall be acquired, maintained, preserved, retained, and used only for the following purposes:

Preservation or restoration of natural areas characterized by or including terrain, geologic formations, flora, or fauna that is unusual, spectacular, historically important, scientifically valuable, or unique, or that represent outstanding or rare examples of native species;

Preservation of water resources in their natural or traditional state, scenic areas or vistas, wildlife habitats, or fragile ecosystems;

Preservation of land for passive recreation use, such as hiking, photography or nature studies, and if specifically designated, bicycling, horseback riding, or fishing;

Preservation of agricultural uses and land suitable for agricultural production;

Utilization of land for shaping the development of the city, limiting urban sprawl and disciplining growth;

Utilization of non-urban land for spatial definition of urban areas;

Utilization of land to prevent encroachment on floodplains; and

Preservation of land for its aesthetic or passive recreational value and its contribution to the quality of life of the community.

Over 45,000 acres of land is administered by OSMP, some of it purchased outright, and some protected by some type of conservation easement. Open Space provides 144 miles of trails, and Boulder’s citizens have increasingly viewed recreational uses of open space as a critical purpose of the system (2004 Attitudinal Survey).

OSMP is funded 90% by dedicated sales taxes (Financial Overview, 2008). A 0.40% tax was passed in 1967 by a 61% margin, and several additional dedicated sales tax increments have been passed, mainly for acquisitions. The incremental sales tax increases are generally scheduled to expire in conjunction with completion of the Open Space Acquisition Plan, which has less than 7,000 acres remaining as targets for acquisition.

In terms of meeting the needs of a denser city, open space acquisitions, particularly of lands suitable for recreational use, are nearing an end. Boulder will have to live with the open space it has already purchased. The remaining 0.40% sales tax will be dedicated to managing the land acquired in the past.

OSMP receives some funds from the Colorado lottery, for which it competes with the Parks and Recreation Department. As a result of the merger of the Mountain Parks in 2001, some funds are supposed to be transferred from the general fund to cover maintenance of the trails that were formerly in the Parks Department budget, but this commitment has never been fully funded, and the recent budget crisis has reduced it further.

Increasing Demands and Pressures

Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks lands are known and loved far beyond the population of the city. They are a destination of choice for users from throughout Boulder County, the Denver metropolitan area, and many other places. The result is a flood of visitors whose objective is to climb, hike, bird watch, mountain bike, or walk their dogs on OSMP lands. Visitation had reached nearly 5 million visitor days a year in 2004-05 (Vaske et al., 2009). Measurements are not strictly comparable, but this is a visitor load larger than that of Rocky Mountain or Yosemite National Parks, concentrated in a much smaller area, with far fewer trail miles. Obviously, these visitors are not all Boulder residents, and anecdotal reports suggest that at the southern trailheads, more and more users come from the Denver metropolitan area outside Boulder County. At major trailheads six or seven years ago, however, 81% of users said they were from Boulder County (Vaske and Donnelly, 2008).

This heavy use creates an enormous challenge, both for funding and for management that is charged with preserving the natural systems in perpetuity (1968 City Council Resolution #24).

Whenever these issues are discussed, suggestions are made that the City should recoup some of the costs of maintaining open space from out-of-town visitors, particularly those not contributing to sales taxes through Boulder businesses. Since there are currently at least 236 publicly accessible, widely dispersed access points to OSMP lands (Vaske et al., 2009), this would not be feasible without major changes to accessibility. Expenses for collection and enforcement also present major obstacles.

Finally, in addition to the increasing view among Boulder residents that recreational use of open space is its most important purpose, there are increasing demands to accommodate new activities, such as mountain biking, on open space lands, which may conflict with current uses.

Summary

The unique open space preserved by the citizens of Boulder over the years has long been one of the major attractions of Boulder and a source of pride in the community.

The challenges of preserving the quality both of ecosystems on OSMP lands and the quality of the visitor experience is difficult for many reasons, and these challenges will become more acute with the growth in population throughout the metropolitan area, not just in Boulder or Boulder County. The demand for experience of a natural environment close to the city will grow with population pressures, environmental change, and growth of the student population at the University of Colorado.

The challenges can only be exacerbated by increased density in the City of Boulder. More dense housing means that the opportunity to get outside increasingly can only be satisfied by using public spaces, which increases pressures on both city parks and on open space lands.

Since it is difficult to add new city parks while increasing population density, and very little new open space can be added to the City of Boulder, these are services where growth really cannot pay its own way. Increased population density will entail degradation of these services and of the quality of life for Boulder residents. Eventually, some measures to limit usage will have to be implemented.

Recent budget shortfalls in the Boulder Valley School District (BVSD) have brought attention to the issue of funding in local schools. State law forbids school districts, cities, and counties from imposing school impact fees on new development. Although the City of Boulder once had an Education Excise Tax that was intended to substitute for such impact fees, the tax was recently suspended because it was not achieving its planned purpose. In absence of a funding source, we can expect BVSD to put a bond issue on the ballot to pay for new facilities in the future, especially in East Boulder County where much of the residential growth is expected to take place. This places the funding burden on existing property owners rather than the new development.

The 2002 drought was a shock to many Boulder residents who had become used to unlimited supplies of water for irrigation and indoor use. Unlike other Front Range cities that regularly impose watering restrictions, Boulder seemed to always have adequate supply. Were the 2002 watering restrictions a consequence of growth or a meteorological fluke? The answer is probably “both.”

During 2002, supplies were extremely low (1 in 300 year streamflows), and the summer particularly dry. Landscaping suffered and some trees were lost. In August of that year, under community pressure, the City modified the watering restrictions to allow limited, deep watering of trees.

With watering restrictions, Boulder was able to deliver 20,770 acre-feet of water to its service area customers in 2002. If the drought had happened in the 1980’s, instead of the 2000’s, full delivery might have been possible. Demand for water fluctuates, and there was a significant decrease immediately after the 2002 drought, but in general, with increasing population, Boulder’s water use has been increasing. Water demands are projected to reach 24,159 acre-feet by 2020.

Figure 6. Boulder’s Total Treated Water Use, 1971-2007

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, Volume 2, 2009

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, Volume 2, 2009

Supplies

From a water supply perspective, Boulder is in much better shape than many Front Range cities. First, Boulder’s water rights portfolio contains very senior rights, meaning that shortages will be imposed on more junior rights before Boulder feels the pinch. For example, according to the Source Water Master Plan, 2009, “even in 2002, when natural flows were less than 50 percent of average, Boulder’s direct flow rights yielded 88 percent of their average.” These water rights provide about 70% of Boulder’s treated water supply. Second, Boulder has redundancy built into its system — it receives water from two different basins: the Boulder Creek basin and the Colorado River basin via the Colorado-Big Thompson (CBT) project. The CBT project provides about 30% of Boulder’s treated water supply.* In contrast, the City of Aurora receives nearly all of its surface water via the South Platte River at a single diversion point. Boulder also has significant storage facilities for a city of its size.

What are the vulnerabilities in Boulder’s water supply system? Of obvious concern is climate change. The City, in cooperation with a number of consultants and scientists, conducted a study for NOAA of the impacts of climate change on the City’s ability to meet its projected water demands at “buildout.” That study found that, under worst case scenarios with full buildout demands, the “potential for violating drought criteria rise[s]” (Smith, et al., 2009).

Another vulnerability hinges on Boulder’s dependence on west slope water. The west slope is in the Colorado River basin and as such is subject to the Colorado River Compact. In the future, increasing demands for water in Lower Basin states (New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California) combined with long term drought could compel one or more Lower Basin states to invoke a “Compact Call” forcing many Upper Basin (Utah, Wyoming and Colorado) water users to bypass water that would normally be stored or diverted. Since a significant portion of Boulder’s water supply comes from the Colorado River basin, a Compact Call could have a large, negative impact.

Finally, Boulder’s population density actually reduces its drought response flexibility. Under drought conditions in most communities, cutting back outdoor water use is usually sufficient and indoor uses are protected. However, unlike most Front Range cities, Boulder’s water use is about 2/3 indoor and 1/3 outdoor. In other cities the ratio is reversed. Since the majority of Boulder’s water use is already indoor use, watering restrictions, as a drought response tool, are less powerful.

Perhaps not in the category of vulnerability, but annexation and development of rural properties by the City will require replacement of ditch irrigation (or no irrigation) with treated water for whatever uses are allowed, placing an additional burden on both capacity and supply.

Funding

Unlike our use of libraries and emergency services, we pay directly, every month, for our water use, and the rate we pay has some relation to the amount of water we use and the cost to provide that water. The City of Boulder provides water, sewer and stormwater services through the Utilities Division of the Public Works Department. To pay for these services the City assesses both user fees (water rates) and development fees. The bulk (76%) of the City’s water utility funding comes from user fees, with development fees being the next largest source of funding at 9%.

Figure 7. Water Utility Funding Sources

Source: City of Boulder Source Water Master Plan, April 2009, Volume 1

The revenues from water rates are used to pay for daily operations and maintenance and for repair and replacement of aging facilities. Development fees are used to pay for increasing facility capacities in the system. Water Plant Investment Fees (PIF) start at $9,282 for a new single family home and increase with irrigated area on the lot. The wastewater PIF for a new single family home is $3,356 and the stormwater PIF is $1.37 per square foot of impervious area. Development fees are being used to pay for recent pipeline and treatment capacity expansions. Further capacity expansions to meet future demands are not expected.

Following the drought of 2002, per capita water use dropped about 20%. Long-term behavior and fixture (toilets, shower heads) changes may have set in. This reduction in water demand is resulting in reduced revenues to the water utility, which has primarily fixed costs. However, studies have shown that water use is higher in higher income households. According to the City’s Source Water Master Plan, “If the average income in Boulder continues to increase, it may also affect residential water users’ habits and preferences, although it is difficult to predict in what way. Installation of backyard fountains and water features often occurs at higher income levels. Water intensive indoor plumbing features, such as soaking tubs and rain showerheads, are often favored in more expensive homes.”

Summary

Because of aggressive and visionary water acquisition efforts since Boulder’s founding, Boulder is in a relatively good water supply position. Development impact fees have paid to increase capacity and users are billed for water delivery. However, growth cannot produce more precipitation. With or without climate change, as the population increases, and water demand grows, Boulder can expect more periods of watering restrictions, more periods of depleted streamflows, more impacts to aquatic and riparian ecosystems, and fewer stream-based recreational opportunities.

The City of Boulder has a Transportation Master Plan that identifies expected transportation levels of services and funding sources to pay for improvements. Close analysis of the TMP, however, reveals that current funding structures do not begin to approach the amount needed to maintain the level of services. The City’s web site states that transportation congestion and delays escalate massively, even at maximum levels of proposed funding. As indicated in the City’s own materials, the current version of the TMP would have Boulder become hugely congested, even if the City had the hundreds of millions of dollars that the TMP budget is projected to be short.

The City staff’s current proposal to tax all property owners to pay for the costs of needed transportation facilities is not only inequitable, but is inefficient, as it provides no incentive to actually reduce driving as a parking charge would. A more equitable source of funding would be development impact fees and excise taxes to deal with the impacts of growth, and parking charges to handle increased operation and maintenance costs. Unfortunately, the Transportation Excise Tax — despite recent increases — is still inadequate to deal with the impacts of additional traffic caused by new development. In addition, the TMP fails to adequately manage the demand for transportation as it avoids strategies that directly reduce driving such as expanding managed parking in employment areas in East Boulder or requiring new developments to offset their vehicle trips.

Because Boulder is committed to alternative modes rather than expanding the street network, impact fees are not a solution, as by state law they can only be used for capital facilities. Alternative modes are operating cost intensive. The solution is to use the Fort Collins “adequate public facilities” approach as a legal basis and apply it to the City of Boulder’s goal. New development would be required to prevent the deterioration of levels of service by offsetting its additional trips, which could be done by having new developments paying existing developments to car pool or van pool or by subsidizing delivery services, and so on.

Many municipalities add more housing and commercial development with the intention of generating tax revenues and/or impact and development fees. Since the City of Boulder does not collect sufficient development fees to fully maintain its per capita level of service, adding population under the current impact fee system will result in lowered levels of service to existing residents for everything from water to emergency services. Further, although historically Boulder residents and businesses have benefited from tax revenues from regional shopping, adding more residents will dilute this revenue pool on a per capita basis, resulting in even lower levels of city services.

There is widespread belief that if development fees were increased, the housing stock in Boulder would become more expensive, further exacerbating the affordable housing issue. It is likely that initially an increase in development charges would impose a burden on individuals who bought property contingent on previous low levels of these fees. In turn, a sharp increase in fees would be a hardship on the developers who bought property counting on not having growth being required to pay its own way.

If new development fees were phased in over time, however, the increases in development fees would not increase the final sales prices and thus not adversely affect these developers. In fact, these fees would just push the price of developable land down. This is because regional markets set the final sales prices of new homes. The final sales price is composed of the cost of land value and the cost to develop that land. If the cost to develop the land were to increase, the value of the land would decrease. Thus, over time increased development fees are less likely to fall on the purchasers (i.e. new residents looking to buy a home in Boulder) but rather will fall on the real estate speculators. One interesting analysis (Pomerance) shows that if the full costs of growth were charged, green field land would sell for not much over its agricultural value, which would allow local agriculture to be preserved.

The municipalities within Boulder County should pass impact fees, excise taxes and/or Adequate Public Facilities ordinances that take into account all of the real impacts of growth. Impact fees should be set at the full cost of adding capital facilities sufficient to maintain levels of service. Adequate Public Facilities ordinances should also set levels of service standards. When a new development is proposed, the municipality would evaluate the impacts on all services and if any are pushed below the standard, the proposed development would be required to invest an amount adequate to bring the level of service back up to standard, or the development permit would be denied. This approach is especially valuable in transportation where the solution to a potential increase in traffic may be an investment in an operating-cost intensive approach like transit rather than a capital-cost intensive approach like adding turn lanes.

Applying the goals of the BVCP to all of Boulder County could create a template for sustainable growth in the county. Unfortunately, the current level of impact fees and development excise taxes are inadequate to achieve these policy goals.

* Additional CBT water is released to Boulder Creek below Boulder to allow the City to take advantage of exchange opportunities and divert additional Boulder Creek flows upstream. When this use is included, CBT water makes up about 50% of Boulder’s supply.