Note: This article is part of a series of 2018 ballot issue analyses written for the Blue Line by author Richard Valenty. You can find coverage of the other 2018 ballot issues here. Ed.

Normally, statewide ballot issues are not of substantially greater interest to Boulder County than to the rest of the state. That may not be the case in the battle between Proposition 112 and Amendment 74, which primarily, but not exclusively, pertain to oil and gas exploration. The results of these measures could have sizable impacts in other counties statewide, but could definitely impact Boulder County very heavily one way or another.

Some people will naturally view these ballot measures from one of two frames—environmental/health protection or business/financial interests. However, there are pages and pages of detail that a voter might wish to know about the finer points of these issues, and this article will supply information plus links for additional reading.

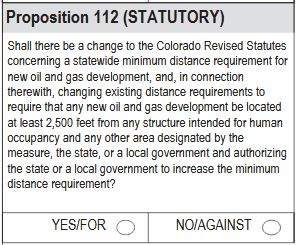

Proposition 112: 2,500-foot Setbacks

Your ballot title will say Colorado Proposition 112 is a statutory measure with two provisions related to oil and gas development minimum distances:

- Require any new oil or gas development in Colorado to be located at least 2,500 feet from any structure intended for human occupancy and any other area designated by the measure, the state, or a local government.

- Authorize the state or a local government to increase the minimum distance requirement.

This might be enough information for some voters to make their decision, but the state Blue Book section on 112 alone adds four pages to the discussion, and reading all the studies and news and opinions could keep a person busy well into 2019. But this election’s over on Nov. 6, 2018, so let’s focus on a few subcategories.

Land Use

Yes, Prop 112 touches on Boulder locals’ favorite topic—land use. Perhaps the most basic tangible development, should 112 pass, would be to keep new wellbores at least 2,500 feet from buildings or vulnerable areas (defined in the next section below). However, this is not 2,500 feet in only one direction—the setback requirement would be in all directions from buildings or vulnerable areas.

Current state setbacks are 500 feet from homes, and 1,000 feet for “high-occupancy buildings” such as schools, hospitals, correctional facilities, and child care centers, as well as neighborhoods with at least 22 buildings. Since these setbacks are in all directions, 500-foot setbacks cover 18 acres, 1,000-foot setbacks cover 72 acres, and 2,500-foot setbacks would cover 450 acres, according to the Blue Book. Also, Prop 112 does not apply to federal land.

The above paragraph illustrates why 112 opponents say very high percentages of the remaining land would be off-limits to new oil and gas development if 112 passes. For example, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) released an assessment in July 2018 saying up to 85 percent of non-federal land in Colorado would be closed off under 112.

However, it is possible to locate a wellbore 2,500 feet or more from a building or vulnerable area and still access oil or gas that would be closer than 2,500 feet if the drilling went straight down. The practice of “horizontal drilling” can access oil or gas in which the underground resources are closer to a building or vulnerable area, though horizontal drilling is more expensive.

Colorado School of Mines associate professor of economics Peter Maniloff recently released a report titled “A Note on the Impacts of Proposition 112.” According to his report, 42 percent of the subsurface would be available for new oil and gas exploration, using the assumption that companies could access natural resources up to a mile away from wellbores through horizontal drilling. Maniloff’s report suggests nearly three times the potential subsurface availability, as a percentage, than COGCC’s assessment of 15 percent surface availability.

Prop 112 would also allow local governments to enact setbacks that are more than 2,500 feet. If two or more local governments with jurisdiction over the same geographic area establish different buffer zone distances, the larger buffer zone governs.

In addition to setbacks between wellbores and buildings or water sources, 112 also pertains to any type of new oil and gas development, including flowlines between oil and natural gas facilities, the treatment of associated waste, or entering abandoned wells.

What Is a “Vulnerable Area?”

According to Prop 112 text, the new setbacks would apply to buildings but also to “vulnerable areas,” including “playgrounds, permanent sports fields, amphitheaters, public parks, public open space, public and community drinking water sources, irrigation canals, reservoirs, lakes, rivers, perennial or intermittent streams, and creeks, and any additional vulnerable areas designated by the state or a local government.”

Negative Environmental and Health Factors

The environmental and health impacts of living near a fracking operation, or siting operations near vulnerable areas like lakes or streams, probably represent the strongest concerns of most 112 proponents. There is also a tremendous amount of information out there. Readers can get their info from ultra-geeky studies, from 112 proponent or opponent web sites that are likely to be largely one-sided, from activists or industry professionals who might also be opinionated, or from TV commercials that always seem to feature women and children playing in lush suburban back yards telling us that fracking is safe. The impacts listed below include links to some of the sources out of the many that are available, but isn’t intended to supply a complete list of all possible impacts. Those looking for opposing views can find other reports on the Coloradans for Responsible Energy Development website.

- Fracking contributes to air pollution, which may impact people living closer to the wellbore more than those living farther away.

- Fracking fluid may contaminate groundwater.

- According to the Denver Post, there were 619 Colorado spills reported to COGCC in 2017, with 93,000 gallons of oil spilled into soil, groundwater and streams, along with 506,000 gallons of “produced water,” waste from drilling and hydraulic fracturing that emerges from deep underground and contains chemicals. This follows 529 spills in 2016, 792 in 2014 and 624 in 2015.

- High-pressure wastewater disposal may contribute to induced earthquakes.

- Exposure to pollutants for those living near a fracking operation may have negative impacts on the health of fetuses and infants.

- Fracking operations can release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas and the primary component of natural gas, into the atmosphere. (Colorado has adopted methane capture rules requiring companies to “find and fix methane leaks and install equipment to capture most of the emissions,” according to the Denver Post.)

Natural Gas Environmental Positives

While Boulder County and Colorado are steadily increasing solar and wind energy generation, the state still relies heavily on fossil fuels for electricity. According to the Governor’s Energy Office, more than 23 percent of electricity generated in Colorado was natural gas-fueled in 2016. Coal still ranked number one at about 55%, and burning coal can release particulates into the air, along with mercury, lead, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, particulates, and various other heavy metals, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. Coal-burning plants can be retrofitted to limit harmful emissions, but these retrofits are costly and certain utilities might choose to shutter coal plants rather than spend the money to retrofit.

In Colorado and nationwide, natural gas has cut into coal’s market share for electric generation, primarily for cost and environmental reasons. The State of Colorado passed the “Clean Air, Clean Jobs Act” in 2009, which in part called for transitioning coal-fired facilities to natural gas. For example, the Valmont plant east of the Boulder city limits stopped burning coal in March 2017, while natural gas-fueled generation continues.

Coal ash (a byproduct of burning coal) can foul water sources, and burning coal releases carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that can contribute to climate change. Coal ash may contain “amounts of silicon dioxide (SiO2), aluminum oxide (Al2O3), and calcium oxide (CaO), as well as traces of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury,” according to a Boulder County report on the Valmont plant.

Also, certain vehicles run on compressed natural gas. According to the Colorado Energy Office, this reduces smog-forming emissions compared to petroleum by 20-45%.

Can We Just Get to 100% Renewable Energy?

Colorado voters passed the first voter-approved renewable energy standard in the nation in 2004, setting the state’s standard at 10%. Also, the state General Assembly has passed subsequent bills increasing the investor-owned utility renewable standard to 30%, and setting electric co-ops at 20%. While many public officials speak about much higher future renewable standards, the state’s current renewable energy portfolio, including hydroelectric, is about 23%. Xcel Energy, the largest investor-owned utility operating in the state, has released a plan that includes a goal of 55% renewables by 2026, but Xcel does not provide electricity statewide.

In short, Colorado is nowhere near 100% renewable yet. While wind and solar prices per kilowatt-hour are decreasing, new wind turbines, solar arrays, transmission lines and other needs still cost significant money.

What Are the Economic Factors?

Colorado clearly has natural gas resources. According to the Colorado Energy Office, in 2016 Colorado ranked 6th among U.S. states in marketed natural gas, producing more than 1.7 million cubic feet, and had the third-largest gas reserves in the country.

The possible economic impacts of Prop 112 are subject to debate, and claims might depend on detail or who’s providing the information. The Colorado Petroleum Council released a study in 2017 saying 232,900 Colorado jobs were “directly or indirectly attributable” to oil and gas in 2015, which contributed $31.38 billion to the state’s economy. However, some of the job categories might not be dependent on Prop 112 results, such as asphalt shingle production or gas station operations.

Nonetheless, it is common for industry sectors to include indirect jobs as part of an employment report. A recent study from the Common Sense Policy Roundtable suggested that passing 112 might cost the state up to 43,000 jobs in the first year. However, its chart on employment impact by sector had only 23 percent for oil and gas extraction, followed in order by: retail trade; professional, scientific, and technical services; health care and social assistance; construction; accommodation and food services; state and local government; other services; administrative, support, waste management, and remediation services; real estate and rental and leasing; and “all other industries.”

On the other side, current economic activity related to fracking may not translate into long-term viability. A recent New York Times story detailed some of the financial challenges, including steep production decline rates for new wells, and high levels of debt allowing companies to remain in operation.

Oil and gas in Colorado has also been subject over time to boom and bust cycles, including times where the pricing of resources relative to the cost of operations made new exploration less profitable. The pro-112 campaign notes that “including related businesses, oil and gas employs less than 1% of the state’s workforce.”

Obviously, some areas of the state currently have more oil and gas activity than others. The Daily Camera recently ran a story called “A Tale of Two Counties…,” detailing differences between how Boulder County and its neighbor, Weld County, regard and value oil and gas. In short, the story reported that Weld had 12,486 oil and gas jobs in the first quarter of this year, according to the state Department of Labor and Employment, while Boulder County had less than 100. Not surprisingly, the Weld County Commissioners do not support Prop 112, while the Boulder County Commissioners do.

Why Hasn’t the State Legislature Taken Care of This Already?

Colorado energy laws are primarily found in state statutes, while COGCC has the authority to promulgate rules that, in short, regulate oil and gas operations. COGCC established the state’s current 500/1,000 foot setbacks through the rulemaking process. State legislators can propose new oil and gas laws, but in recent years proposed laws of significant impact have had little chance of passing. Bills such as HB 17-1256 and 18-1352 would have expanded the setbacks for schools to include the property boundary, not just the building. HB 18-1355 and 18-048 pertained to local control. The bills all died.

Opponents to 112 will say the state already has stringent oil and gas laws, and some will claim they’re the toughest in the nation. Without getting into rankings, readers can examine Colorado Revised Statutes Title 34, and scroll down to section 60, to check what’s already on the books, and after finishing, readers can go back to the COGCC website and look through established rules.

The state’s initiative process allows citizens to run an issue by the voters if the legislature can’t or won’t do what they want. For example, Amendment 37 established our first renewable energy standard, but it came after the legislature defeated bills several years in a row. Prop 112 supporters are following a similar path.

Proposition 112 Pros and Cons

Pro

- Health is a primary human concern, and studies have shown potential health impacts to families living near oil and gas operations.

- Fracking waste is a pollutant, and high-pressure fluid injection has been linked to earthquakes.

- Oil and gas companies may increase exploration within Boulder County, putting locals at greater risk for health or quality of life impacts.

- Companies may still be able to explore for oil and gas despite new setback requirements, by using horizontal drilling.

- We should increase our use of renewable energy and electric vehicles, not rely on fossil fuels.

Con

- The setbacks proposed under 112 are much larger than current law, and may put much of the state off-limits to new exploration.

- Colorado has historically been an extractive industry state, and these industries provide natural resources, jobs, and economic activity, all of which Prop 112 could impact.

- Oil and gas activity within the U.S. can decrease our reliance on resources from foreign nations.

- We’re not ready for 100% renewable energy, so we’ll need fossil fuels if we want to maintain relevant parts of our standard of living.

On the Web

Proposition 112 proponents: https://corising.org

Proposition 112 opponents: https://www.protectcolorado.com

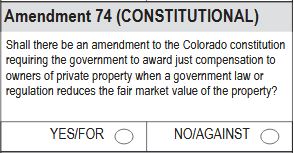

Amendment 74: Governments Liable for Fair Market Value

State Amendment 74, as the name suggests, would amend the Colorado Constitution by adding 11 words to the existing section on “takings,” found in Article II, section 15. The 11 words are bold-faced within this sentence from the initiative text: “Private property shall not be taken or damaged, or reduced in fair market value by government law or regulation for public or private use, without just compensation.”

While this is not a large volume of wording to add to our voluminous Constitution, the impact, if 74 passes, could be immense. As a measure that adds to our Constitution, it will require 55 percent voter approval to pass, and would require another successful ballot initiative or a successful court challenge to be overturned.

Amendment 74 could easily be seen as an attempt to prevent or minimize restrictions on oil or gas development. Ballotpedia quoted a registered proponent for 74, Chad Vorthmann of the Colorado Farm Bureau, as saying, “These measures are about protecting Colorado’s farmers and ranchers from extremist attempts to enforce random setback requirements for oil and natural gas development.”

However, neither the initiative text nor the ballot title limits consideration of reduction in fair market value to oil and gas operations alone. Opponents of 74 say this would open the doors for property owners to sue over a wide range of government decisions that could be seen as reducing fair market value of a property holding. For example, Boulder locals could easily imagine a property owner suing a local government for limiting development on his or her site. Or, a local government’s decision to disallow a type of commercial facility due to health, safety, or aesthetic reasons could trigger a lawsuit against said government.

Even if property owners were to only invoke 74 in case of oil and gas exploration, the results could be especially harmful to the Boulder County government and municipal governments within the county that might try to enact fracking moratoriums. Many Boulderites have read the recent story “A Tale of Two Counties…” about the differences between Boulder and Weld counties when it comes to approving or favoring oil and gas exploration. Boulder County has taken oil and gas action in the past; it seems far more likely to take action again in the future than a top natural gas-producing county like Weld, and therefore seems more likely to face lawsuits under 74 than Weld County.

The financial penalties of a successful lawsuit could range from significant to disastrous for a government, depending on factors such as the size of the settlement, the size of the government, or its financial reserves. While not all lawsuits are successful, governments could also face legal expenses in attempting to stave them off in court.

The most common historical example cited in opposition to 74 is from Oregon’s experience. In 2004, Oregon’s Ballot Measure 37 passed, but it was overturned just three years later with Measure 49. A single paragraph on 37 in “Ballot Measures 37 (2004) and 49 (2007) Outcomes and Effects” from the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development sums up some of the problems in a few sentences:

“The effect that Measure 37 had on the land use program cannot be overstated. The measure itself was brief at 1½ pages, and contained many ambiguities. State and local government were faced with carrying out a voter-approved mandate with no clear procedures and virtually no legislative guidance. The potential consequences of a misstep were enormous in terms of liability – the measure gave property owners the ability to collect monetary compensation unless government acted within 180 days of the filing of a claim, and the total amount of claims exceeded $17 billion.” (Emphasis added.)

Large-scale anti-fracking sentiment is a relatively new phenomenon, historically speaking. With the relatively new calls for setbacks or local control have come proposals for bills to, like Amendment 74, hold local governments liable for impacts to fair market value. For example, this year’s Colorado General Assembly deliberated on House Bill 18-1150 and Senate Bill 18-009 (basically the same bill in both chambers), but both bills were defeated in committee. Readers shouldn’t be surprised to see similar bills again in 2019 if Amendment 74 doesn’t pass.

Amendment 74 Pros and Cons

Pro

- Owners of mineral rights and property owners have reasonable expectations of return on their investments.

- Oil and gas exploration can contribute to jobs and economic activity, also reducing US reliance on foreign sources of fuels.

- It’s possible for a local government to overreach with regulations, and Prop 74 would provide aggrieved property owners with a path for recourse.

Con

- Health and safety for residents of a community is a primary concern, and a legitimate reason for government action despite all other factors.

- The amendment language does not limit lawsuits to being over oil and gas only, so lawsuits might take place over issues such as zoning or commercial development denials.

- Successful lawsuits could damage the ability of a local government to meet its other responsibilities, and even unsuccessful lawsuits may cut into fiscal sustainability.

- In worst-case scenarios, the financial damages to a government could be catastrophic.

- The threat of being sued may persuade certain governments from making otherwise prudent decisions.

- Amendment 74 would go in the state Constitution, meaning it could not be amended without going back to voters.

On the Web

Proponents of Amendment 74: https://coloradosharedheritage.com/

Opponents of Amendment 74: https://no74.co/