The most important task of the urbanist is controlling size.

—David Mohney

As owners of the Boulder Community Hospital (BCH) site bounded by Broadway, Alpine, 9th Street, and Balsam, the City of Boulder has a golden opportunity to demonstrate the preferred vision for creating compact, walkable development in appropriate locations within Boulder. The redevelopment project is called Alpine-Balsam.

For too long, citizens have rightly attacked many new projects in Boulder. We now have a chance to show how to do it right.

The following is one man’s opinion about how we can do it right at the BCH site.

First Determine the Context

Our very first task in establishing a “How to Do It Right” vision is to determine the “context” of the site. Where is it located in the community? Is it a walkable town center? A drivable suburb? A farmable rural area? Only when we answer that question are we able to know which design tactics are appropriate and which are inappropriate. For example, if we are in a suburban context, it is inappropriate to insert shops and offices within the neighborhood, or use small building setbacks. However, if we are in a town center context, those design tactics are entirely appropriate and desirable.

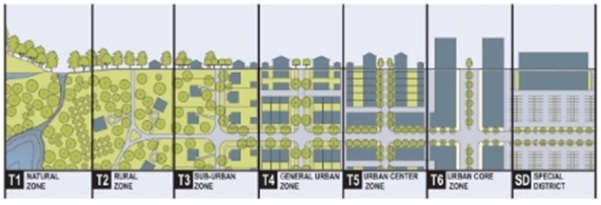

Rural to Urban Transect. Image credit: Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company

In the case of the BCH site, it is generally agreed by the city that the context is walkable town center (what is called “Urban Center Zone” in the above figure). It is now important, given that, to ensure that the design of the site is compatible with that vision.

How do we do that?

A Form-Based Code

Perhaps the most effective way to do that is to establish what is called a “form-based code” (FBC) or a subcommunity overlay plan, which was successfully used to guide the development of the Holiday neighborhood in North Boulder.

The FBC or plan emphasizes the importance of “form” by specifying the appropriate and desirable building placements, street dimensions, and building materials. This differs from the conventional “use-based” zoning codes, which over-emphasize the importance of uses within a building, and only specify designs and dimensions that are prohibited, rather than specifying what is desired by the community.

As Andres Duany notes[1]…

…A FBC protects us from the tendency of modern designers to disregard timeless design principles in favor of “anything goes.” An “anything goes” ideology too often leads to “kitschy” buildings, unwalkable streets, and other aspects of low-quality urban design.

…A FBC protects us from the whims of boards and committees.

…A FBC is necessary so that the “various professions that affect urbanism will act with unity of purpose.” Without integrated codes, architects, civil engineers and landscape architects can undermine each others’ intentions by suboptimizing.

…A FBC is necessary because without it, buildings and streets are “shaped not by urban designers but by fire marshals, civil engineers, poverty advocates, market experts, accessibility standards, materials suppliers and liability attorneys” —none of whom tend to know or care about urban design.

…A FBC is necessary because “unguided neighborhood design tends, not to vitality, but to socioeconomic monocultures.” The wealthy, the middle-class, and the poor segregate from each other, as do shops and restaurants, offices, and manufacturing. A FBC can ensure a level of diversity without which walkability wilts.

…A FBC is necessary to reign in the tendency of contemporary architects to design “look at me” buildings that disrupt the urban fabric.

…A FBC is necessary to ensure that locally appropriate, traditional design is employed, rather than “Anywhere USA” design.

…A FBC is needed to protect against the tendency to suburbanize places that are intended to provide compact, walkable urbanism.

…A FBC is necessary to protect against the tendency to over-use greenery in inappropriate places such as walkable town centers. In particular, grass areas tend to be inappropriate in walkable centers. Over-using greenery is a common mistake that tends to undermine walkability.

…A FBC is needed because codes “can compensate for deficient professional training. Because schools continue to educate architects towards self-expression rather than towards context, to individual building rather than to the whole.”

We can craft a FBC in hands-on workshops driven by citizens and urban designers. When crafting a FBC, such workshops are called “charrettes,” where professional urban designers provide attendees with a one- or multi-day training course in the time-tested design principles of creating a successful town center, suburb, or rural area. Armed with such knowledge, citizens and designers craft a FBC that is appropriate for the context and community values.

Designing the BCH Site

The following are my own individual suggestions for a FBC that would employ time-tested principles for creating a successful walkable, lovable, charming town center.

The overall layout is compact and walkable. For example, building setbacks are human-scaled and quite modest. Private front and backyards are similarly small in size. Public parks are smaller pocket parks rather than larger, suburban, fields of grass (note that abundant grass and athletic fields are provided just west of, and adjacent to, the BCH site). Some of these parks are relatively small public squares formed by buildings that face the square on all four sides. If surface parking is unavoidable at the site (and I would very strongly urge against such parking), the parking should be designed as a public square that occasionally accommodates parked cars. Block sizes are relatively small, based on a street grid, and include many intersections. Internal streets and alleys are plentiful and narrow enough to obligate slower, more attentive driving. Give-way streets, slow streets, woonerfs, and walking streets are all appropriate and desirable.

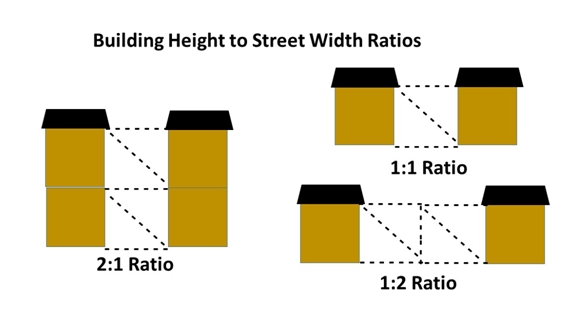

Internal streets should have a spacing of at least one-to-one (or two-to-one or one-to-two) ratio of flanking building height to street width.

Pearl Street Mall is between 1:2 and 1:1 ratio

To promote vibrancy and safety, the city should encourage 24/7 activity by discouraging weekday businesses, such as offices, that close after 5 p.m. Businesses that close after 5 p.m. create night-time dead zones.

Service vehicles that may use streets, such as buses, delivery vehicles, or fire trucks should be small enough that they do not obligate the establishment of overly large streets or intersections. When such vehicles cannot be relatively small, it is appropriate for such vehicles to be required to move more slowly and carefully. Dimensions, in other words, should be human-scaled, not tractor-trailer-scaled.

If feasible, Goose Creek under the BCH site should be daylighted. It would be appropriate to create a bustling, miniature version of the San Antonio Riverwalk, with homes and shops lining the creek. At a minimum, a daylighted creek needs to be relatively permeable with several pedestrian crossings along the way to promote walkability. Since the BCH site is in a compact, walkable zone, wide suburban greenspaces flanking the creek would not be appropriate.

Alignments are more formal and rectilinear. Internal streets, sidewalks and alleys have a straight rather than curvilinear (suburban) trajectory. Street trees along a block face are of the same species (or at least have similar size and shape), have a large enough canopy to shade streets, and should be formally aligned in picturesque straight lines rather than suburban clumps. Building placement is square to streets and squares rather than rotated (to avoid “train wreck” alignment more appropriate for suburbs). Buildings that are rotated rather than parallel to streets and squares are unable to form comfortable spaces.

Streets deploy square curbs and gutters. Stormwater requirements should be relaxed at the site to prevent unwalkable oversizing of facilities. Streets are flanked by sidewalks. Signs used by businesses are kept relatively small in size. For human scale, visual appeal, and protection from weather, shops along the street are encouraged to use canopies, colonnades, arcades, and balconies. When feasible, civic buildings or other structures with strong verticality are used to terminate street vistas.

Turn lanes and slip lanes in streets are not allowed on the site.

Street lights are relatively short in height to create a romantic pedestrian ambiance and signal to motorists that they are in a slow-speed environment. They are full cut-off to avoid light pollution.

Buildings are clad in context-appropriate brick, stone, and wood. Matching the timeless traditional styles of the nearby Mapleton Hill neighborhood is desirable. Building height limit regulations exempt pitched roofs above the top floor of buildings to encourage pitched roof form and discourage the blocky nature of flat roofs. Obelisks and clock towers are also exempt from height limits.

Buildings taller than five stories should be discouraged for a number of reasons. First, they tend to be overwhelming to pedestrian/human scale. Second, they tend to induce excessive amounts of car parking. Finally, if we assume that the demand for floor space is finite at the BCH site, it is much preferable from the standpoint of walkability for there to be, say, 10 buildings that are 5 stories in height rather than 5 buildings that are 10 stories in height.

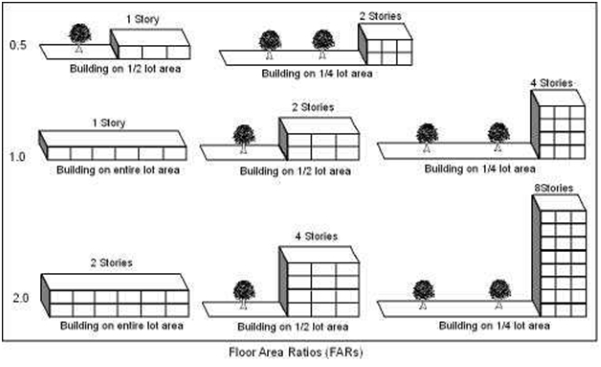

Floor-area-ratio (FAR) is a measure of how much square footage can be built on a given piece of land. A relatively high FAR is supportive of walking, transit, and bicycling. In commercial areas, FAR should be at least 1.0.[2] Richard Untermann, a well-known urban designer, calls for FARs of 2.0-3.0 in town centers.[3]

Buildings along the street are often graced with front porches to promote sociability, citizen surveillance, and visual desirability.

Relatively small offices and retail shops are sensitively interspersed within the neighborhood. For additional walkable access to shops and services, Broadway to the east of the BCH site should incorporate designs which make the crossing more safe and permeable. Narrowing crossing distances and various slow-speed treatments can effectively achieve increased permeability.

First floors of buildings along sidewalks provide ample windows. First floors of buildings are not appropriate places for the parking of cars.

Given the affordable housing crisis in Boulder, ample affordable housing must be provided. Residences above shops are desirable, as are accessory dwelling units and co-ops. An important element in providing affordable housing will be the inclusion of shops, services and offices within the neighborhood, allowing residents to allocate larger proportions of household money to their homes and less to car ownership and maintenance (since the household would be able to shed cars by owning, say, one car instead of two, or two instead of three).

An important way to make housing more affordable is to unbundle the price of parking for residences from the price of housing. Available parking is modest in quantity and hidden away from the street. Parking is space efficient because shared parking is emphasized and tends to be either on-street or within stacked parking garages. No parking is allowed to abut streets, unless the parking is on-street, or in a stacked garage wrapped with retail and services along the street.

The BCH site is exempted from required parking, and is also exempt from landscaping requirements.

Unbundling the price of parking and reducing the land devoted to parking are both important ways to create more affordable housing.

The Washington Village neighborhood project a few blocks to the north on Broadway and Cedar is a good model for appropriately compact and walkable spacing at the BCH site.

Let’s not squander this important opportunity. Let’s insist that we build a neighborhood that fits the pattern of walkable Siena, Italy, not drivable Phoenix Arizona.

[1] “Why We Code,” Sky Studio. http://www.studiosky.co/blog/why-we-code.html

[2] SNO-TRAN. Creating Transportation Choices Through Zoning: A Guide for Snohomish County Communities. Washington State (October 1994)

[3] Untermann, Richard. (1984). Accommodating the Pedestrian, pg. 190.