Editor’s note: Throughout the summer and fall we will run a serialized version of PLAN-Boulder County’s A Transportation Vision for Boulder. This is part 1 of section 2. To read the entire paper, start with the Introduction.

Sizing Streets and Intersections for Safety and Quality of Life

When emergency, service and delivery vehicles are relatively large, the excessive size becomes the “design vehicle” that road engineers use, which ends up driving the dimensions of city streets. Huge vehicles should not be determining the size of our street infrastructure.[1] Street sizing in a town center should instead be based on safety for pedestrians and bicyclists, human scale, and overall quality of life.

Designing for the infrequent large fire truck may, on balance, be more harmful than helpful because it may encourage improper travel behavior by the more frequent users of neighborhood streets: passenger cars. For example, larger trucks often result in the construction of larger turning radii, yet the benefits obtained by the rare truck are outweighed by the frequent auto, which is encouraged to drive faster due to the larger radii. Motorists tend to travel at the maximum speeds they feel are safe; therefore, a street designed for safety at high speeds results in higher average travel speeds. Faster vehicle travel discourages travel by pedestrians and bicyclists, who feel less safe with the higher speed traffic. In addition, the higher average speeds make the neighborhood less livable because the neighborhood not only sees a restriction in travel choice but also suffers from ambient noise level increases.

Peter Swift conducted a study in Longmont, Colorado that found car crashes (and the number of transportation injuries and deaths) increased when cities increased the size of their streets and intersections. Ironically, those increased sizes were often pushed by fire/rescue officials seeking to reduce response times for fire trucks. The Swift study found that the lives saved from reduced response times was far less than the number of lives saved by keeping street dimensions small.[2] Our focus, therefore, should be on life safety, not just fire safety (which is a subset of life safety).

An existing or emerging town center should be designed for human scale and safety, not for the needs of huge trucks. Designing for “possible” (and rare) uses such as large trucks, instead of “reasonably expected uses” such as cars, leads to worst case scenario design—not a proper way to design a livable neighborhood. Over-sized trucks in Boulder can too easily lead the city down a dangerous, backwards path, as street and intersection dimensions are typically driven by the “design vehicle.”

PLAN-Boulder recommends that the city design and maintain smaller, lower-speed street and intersection dimensions in town centers, and move away from using larger vehicles as the design vehicle in those parts of the city. This approach to sizing streets would be most effective if coupled with efforts to control the size of emergency, service and delivery trucks allowed within town centers.

Block Size and Connectivity

Block Size

In existing and emerging Boulder town centers, sidewalks that must wrap around large block faces are an impediment to pedestrian convenience due to the excessive size of the block. Unfortunately, there has been a trend toward longer and longer blocks. The practice of block consolidation contributes to a city scaled to cars and is a grave error if pedestrian friendliness is the goal. Smaller blocks have more intersections, which slow cars to safer speeds and provide more places where cars must stop and pedestrians can cross. Also, short blocks and more frequent cross streets create the potential for walking more directly to the destination (the shortest route, as the crow flies). In addition, a more dense network of streets disperses traffic, so that each street carries less vehicle traffic and can be scaled less as a superhighway and more as a livable space—which makes streets more pleasant and easier to cross. More intersections provide the pedestrian with more freedom and control, since they can take a variety of different routes to their destination. Shorter blocks also make the walk seem less burdensome, since a person can reach “goals” (such as intersections) more quickly. Block lengths in new developments should be no more than 300 to 500 feet in length. If they must be longer, mid-block “cross-access” routes should be created.[3]

One important way to keep blocks short and streets connected is to strive to retain street rights-of-way (ROW). Requests for vacating ROWs must be scrutinized to ensure that they are only granted if there is a clear public interest that outweighs the vital objectives of walkable, bikeable, route-choice-rich neighborhoods.

Connectivity

“One of the most important – but least understood – aspects of architecture and urban design is the extent to which the design and layout of residential streets determines the character and quality of communities – both urban and suburban, new and old. Some patterns create a sense of neighborhood and community, while others foster feelings of separateness and isolation. Some nurture social activity and children’s play, while others lead to heavy traffic and degradation of the environment.”[4]

Connected streets make walking, bicycling, and using the bus more feasible by significantly reducing trip distances and increasing the number of safe and pleasant routes for such travelers. They provide motorists and emergency service vehicles with more “real time” route choices. A route that is impeded or blocked can be avoided in favor of a clear route, which is not possible on a cul-de-sac. In combination with the fact that connected streets distribute vehicle trips more evenly, real time route choices on connected streets durably reduce congestion on collector or arterial roads. As a result of this distribution, there is little or no need for neighborhood-hostile collectors or arterials, which, because of the volume and speed of vehicle trips they carry, are unpleasant for the location of residences.[5]

Compared to connected street networks, cul-de-sac street networks create:

- Travel barriers for pedestrians, bicyclists, and bus riders (connected streets have small, walkable blocks and numerous connections)

- A reduction in “real-time” trip route choices for motorists and emergency vehicles

- Higher average vehicle speeds, but longer average trip time

- A concentration of vehicle trips on major roads, causing more street and intersection congestion (connected streets reduce use of major roads by 75 to 85 percent)

- Increased service costs for postal delivery, garbage pick-up, and the school bus, which leads to higher fees and higher taxes

- A 50-percent increase in vehicle miles traveled

- Social isolation for children, seniors, disabled and low income residents

- An overemphasis on the private realm, which reduces neighborliness and promotes neglect and deterioration of the public realm

- Increased levels of confusion and disorientation about the direction one is heading

Relatively high levels of connectivity are desirable in existing and emerging Boulder town centers. Less street connectivity is more appropriate in Boulder’s drivable suburbs and other outlying areas. Boulder should strive to maximize street connectivity in new developments, and retain connectivity in existing developed areas.

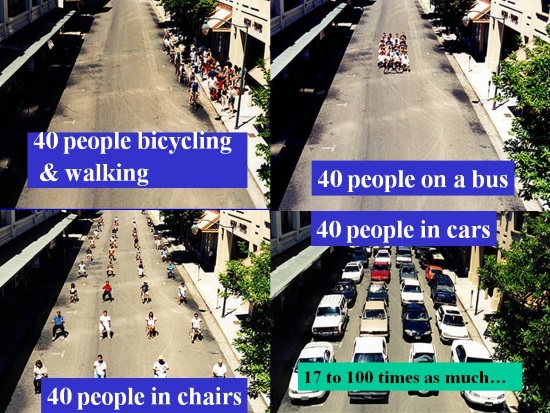

Gigantism

Vast acreages of asphalt and concrete for car travel and storage now cover immense land areas[6] in American cities, including Boulder, and these hard, deadening surfaces continue to spread throughout the city. Why? Because a high percentage of Boulder’s population travels by car, and a person driving in a car consumes as much space as dozens of people biking or walking. Despite all of the admirable things Boulder has done[7], there are still lots of cars in the city consuming a lot of space.

The needs of motorists (mostly lots of road and parking space, and high speeds) and the human-scaled spaces and lower speeds needed for people not driving a car, like on the Pearl Street Mall, are diametrically opposite. When Boulder provides (or allows) this expansive, expensive road and parking lot hardscape for cars, a powerful sprawl dispersant is created.[8]

While it is less of a problem than in most other American cities, Boulder is suffering, to some extent, from a form of gigantism. Gigantic streets, gigantic speeds, gigantic intersections, gigantic parking lots, gigantic subsidies, and what amounts to gigantic sprawl.

A great many citizens of Boulder admirably seek to retain or restore a small town feel (or ambiance) in our community. Many believe that tall, bulky buildings destroy our small town feel. Another important way that small town ambience is undermined is to build oversized roads, intersections, and parking lots. Tragically, Boulder has done this too many times in efforts to reduce congestion or promote free-flowing car traffic. Boulder has oversized a great many of its roads[9] and intersections, and has required developers to build too many oversized parking lots. The end result of the pursuit of free-flowing car traffic is a powerful contribution to a loss of that small town feel—that human scale—that so many in Boulder seek to protect and retain.

Boulder needs to reverse the over-provision of hard surface roads and parking for cars by reforming its inefficient, outdated parking requirements, and by placing a moratorium on increasing the size of intersections and roadways. The city shouldn’t add additional through-lanes, and inappropriate turn lanes should be addressed.[10] Many parking and road facilities need to be right-sized—that is, in nearly all cases, reduced in size.

Small town ambience is undercut by excessively catering to the enormous space needs of cars by creating and widening streets and intersections. Charles Marohn[11] cautions cities not to fall into the downwardly spiraling trap of creating what he calls “stroads.”[12] Stroads fail to be good streets or roads, because when a community oversizes what should be a street in a town center by adding too many travel or turn lanes, the stroad fails to provide what is provided by a quality street: human-scale, a richness in transportation choice, vibrancy, livability, small-scale retail, and slower speeds. Stroads also fail to be quality roads because they become congested and thereby fail to efficiently carry larger volumes of higher-speed regional car trips.

In a town center, we need to let a street be a street by retaining or restoring modest, human-scaled dimensions.

By creating smaller, human-scaled streets and parking, we reduce motorist subsidies, reduce air emissions, reduce injuries and deaths due to traffic crashes, reduce sprawl, improve transit, increase travel choice, provide a broader range of lifestyle choices, promote community financial health, enhance community pride, and improve livability.

Double Left Turn Lanes

Traffic engineers commonly claim that such intersection “improvements” as adding a second left-turn lane will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reducing congestion. Many further believe a double left turn does not conflict with the transportation plan objective of promoting pedestrian and bicycle trips. This is simply not true. It is clear that increasing car-carrying capacity with double left-turn lanes increases emissions and will reduce pedestrian and bicycle trips. Double left-turn lanes have been shown to be much less effective than commonly thought even if we are just looking at car capacity at an intersection. This is because adding a second left turn lane suffers significantly from diminishing returns. A double left turn does not double the left turn capacity—partly because by significantly increasing the crosswalk distance, the car and walk cycle must be so long that intersection capacity/efficiency (for cars) is drastically reduced.[13]

One of the absurdities of installing a second left turn lane is that many cities today regularly cite severe funding shortfalls for transportation, yet these same cities seem eager to build expensive and counterproductive double left-turn lanes. This is probably because transportation capital improvement dollars are in a separate silo than maintenance dollars, and that the former dollars are mostly paid by federal/state grants (which cities naturally consider to be free money). Michael Ronkin, former bicycle/pedestrian coordinator for the State of Oregon, calls double left-turn lanes a sign of failure: failure to provide enough street connectivity. With low connectivity, according to Ronkin, when drivers do come to an intersection, the intersection needs to be gigantic, so it can accommodate all the left turns that had not been allowed prior to that point.

Double left-turn lanes:

- Destroy human scale, a small town feel, and a sense of place

- Increase per capita car travel & and reduce bike/ped/transit trips

- Increase GHG emissions and fuel consumption

- Induce new car trips that were formerly discouraged

- Promote sprawling, dispersed development

- Discourage residential and smaller, locally-owned retail

One specific but little-noted cost of adding a second left-turn lane (and of intersection expansion more generally) is that it can affect signal wait times far away from the expanded intersection. In Boulder, signals in all of the east part of the city are synchronized, according to discussion with the city’s traffic signals engineer. When the city enlarged the Arapahoe-Foothills intersection, including building triple (!) left turn lanes, the increased crossing distance necessitated extending the signal cycle there. That then correspondingly resulted in extended signal cycles all across east Boulder, making the system less friendly for bikes and pedestrians in particular, and also less efficient for cars at low-volume times.

Boulder needs to draw a line in the sand: impose a moratorium on intersection double left-turn lanes and eventually remove such configurations—particularly in the more urbanized portions of the region. One important exception, perhaps in the short term, is the occasional need to retain an existing left turn lane as a way to avoid excessive congestion due to road right-sizing. But in general, double left-turns are too big for the human habitat. They create a car-only atmosphere.

Continue to the section: Urban Design part 2

[1] It is acknowledged that truck deliveries are necessary – even in compact town areas. Fortunately, alleys and truck loading zones can be designed so that we keep narrow streets with small curb radii, but still allow truck access.

[2] http://bettercities.net/news-opinion/blogs/robert-steuteville/21128/bad-call-wide-streets-name-fire-safety

[3] Ewing, Reid. (1996). Pedestrian- and Transit-Friendly Design. Prepared for the Florida Dept. of Transportation, pg. 11; Planners Advisory Service. (1996). Creating Transit-Supportive Land Use Regulations. See also: Planners Advisory Service. (1996). Creating Transit-Supportive Land Use Regulations. #468, pg. 6. The Gainesville Traditional Neighborhood Development ordinance and the Traditional City ordinance both call for a maximum block face length of 480 feet.

[4] Southworth, M. & E. Ben-Joseph. (1997). Streets and the Shaping of Towns and Cities. Preface.

[5] Institute of Transportation Engineers. (1994). Traffic Engineering for Neo-Traditional Neighborhood Design. February 1994. Pg. 5, 8 & 13.

[6] Lester Brown (“Pavement is Replacing the World’s Croplands,” Grist, Mar 1, 2001) estimates that the U.S. area devoted to roads and parking lots covers an estimated 61,000 square miles. For the sake of comparison, Florida is 58,681square miles in size.

[7] Such as the construction of a relatively comprehensive network of on-street and off-street bicycle routes/paths, a relatively high quality bus system, purchase of an enormous greenbelt, successful nurturing of a walkable town center (including a successful pedestrian mall), and a parking cash-out program.

[8] Oversized and underpriced roads and parking disperse a community by enabling residents to live, work and shop in relatively remote locations, while being able to remain within the historic, cross-cultural travel time budget of about 1.1 hours of round-trip travel per day. Indeed, the size of most all communities corresponds to average citizen travel times: Faster travel by car allows one to live in remote locations while still remaining within the travel time budget. Therefore, higher speeds result in a larger, more dispersed geographic footprint for a city.

[9] Although no roadways have had new car travel lanes added in a number of decades.

[10] For the purposes of this paper, the Boulder town center is generally defined by the Central Area General Improvement District (CAGID). Examples of such turn lanes include those where Broadway intersects with Pine, Spruce, and Walnut.

[11] Marohn is a Professional Engineer licensed in the State of Minnesota and a member of the American Institute of Certified Planners. He has a Bachelor’s degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Minnesota’s Institute of Technology and a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey Institute. He is the author of Thoughts on Building Strong Towns (Volume 1), the primary author of the Strong Towns Blog and the host of the Strong Towns Podcast.

[12] See: http://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2013/3/4/the-stroad.html#.U6iV_vldVDw

[13] According to Michael Moule, P.E., president of Livable Streets, Inc. in a personal communication (3/14/15), double-left turns suffer from the following inefficiencies, which is why they do not have double the turning capacity of a single left-turn lane: (1) Poor lane utilization. Double turn lanes are often more susceptible to poor lane usage than through lanes, especially if there is a lane drop soon after the turn, or where there are more destinations on either the right or left side of the road that drivers are turning on to; (2) Friction due to multiple lanes, while turning or otherwise; (3) Lost [green] time overall for the intersection [for cars] due to [the intersection] being bigger. The increased pedestrian clearance time…is the biggest part of this, but bigger intersections also have smaller amounts of lost time in yellow and red clearance intervals; (4) Double-left turns generally must have protected-only signal phasing. Single lefts can have protected-permissive or even permissive-only signal phasing. Protected only phasing is less efficient overall for an intersection.

The mission of PLAN-Boulder County is to ensure environmental sustainability, promote far-sighted, innovative, and sustainable land use and growth patterns, preserve the area’s unique character and desirability, and reduce our carbon footprint and environmental impact.

PLAN-Boulder County envisions Boulder County as mostly rural with open land between cities and towns that support working farms on good agricultural land and provides for conservation of critical habitats for wildlife and native flora. Within Boulder and neighboring communities, urban boundaries limit sprawl and growth is directed to meet community goals of housing affordability, diversity of all kinds, environmental sustainability, neighborhood identity, and a high quality of life. PLAN-Boulder County further supports green building practices that minimize energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, PLAN-Boulder County supports a more balanced transportation system that actively promotes public transit, bicycle commuting, and pedestrian travel, and provides for smarter use of automobiles.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the various city and county organizations with which the authors are affiliated.

Dom Nozzi, principal author of this paper, is a member of the PLAN-Boulder County Board of Directors and the City of Boulder Transportation Advisory Board. Mr. Nozzi has a BA in environmental science from SUNY Plattsburgh and a Master’s in town planning from Florida State Univ. For 20 years, he was a senior planner for Gainesville, Forida and was also a growth rate control planner for Boulder. He has authored several land development regulations for Gainesville, has given over 90 transportation speeches nationwide, and has had several transportation essays published in newspapers and magazines. His books include Road to Ruin and The Car is the Enemy of the City. He is a certified Complete Streets Instructor providing Complete Streets instruction throughout the nation.

Pat Shanks, Jeff McWhirter, Alan Boles and Scott McCarey also contributed to this paper.