The Supreme Court issued momentous decisions this session on the Affordable Care Act and gay marriage. In the shadow of those headline-makers, a decision strengthening the interpretation of the Fair Housing Act went less noticed. But the FHA decision could, in its own way, have as great a long-term effect on American society as the other two higher profile decisions.

At issue in the FHA case was the doctrine of disparate impact. The Fair Housing Act forbids discrimination in housing based on status such as race or gender. But the FHA, like some of its companion legislation from the Civil Rights era, is written in such a way as to leave open the question of whether the prohibition extends beyond intentional discrimination (termed disparate treatment) to policies that do not constitute an intent to discriminate, but that nonetheless affect people differently based on protected class. For instance, if a city’s policy is to put affordable housing in the areas of the city where it’s cheapest to build, and which tend to have higher minority populations, thus unintentionally exacerbating segregation, does this violate the FHA?

Previously, the court had found that the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act do, indeed, provide protection from this sort of disparate impact. In this session’s case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, the court affirmed that that protection extended to the FHA.

In other words, if taken at full value, the court’s decision means that housing policies and regulations that result in de facto racial segregation are prohibited under the FHA. Significant variation in racial makeup across a community or even across a metro region are potentially suspect, particularly if it’s possible to attribute them to specific rules or policies.

Which brings us to Boulder. Needless to say, Boulder is overwhelmingly white. At the time of the 2013 American Community Survey, a total of 894 people in Boulder were African American, or 0.9% of the population. The number is so low that it’s not even possible to do meaningful analysis of variation across the city. Looking metro-wide, this of course begs the question of why the proportion is so low, given, for instance, that African Americans make up 11% of the population in Denver. It’s safe to assume that it’s not because African Americans don’t like having a good view of the Flatirons.

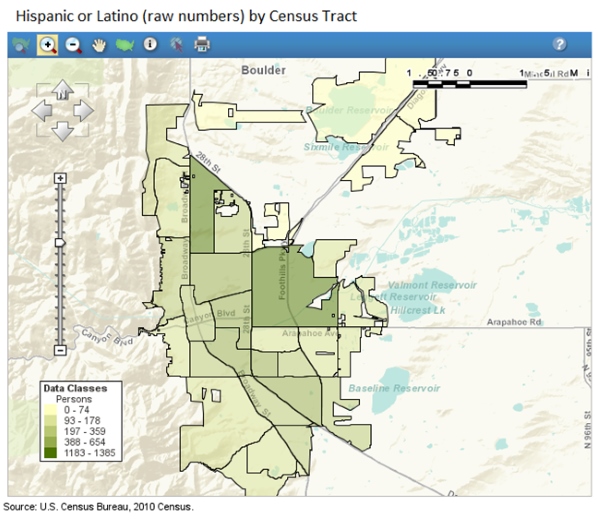

For Hispanics, on the other hand, the numbers are high enough that we can reasonably look at variation within Boulder. It comes as no surprise that the ACS shows huge disparities by census tract, from 3% in Gunbarrel to over 30% in northeast Boulder, with its large Hispanic populations, especially in affordable mobile home parks and at San Juan del Centro.

Hispanics have a median household income (nationwide) 30% less than that of whites, they predominantly live in the parts of the city that are zoned in such a way that they are affordable to those of lower income. So do the city’s zoning policies result in disparate impact? At least on its face, the answer would appear to be yes.

It seems unlikely that the court anytime soon will strike down in a broad way exclusionary zoning policies (like those keeping mobile homes or multi-family housing out of single-family zones), even if they have a history as intentional tools of class segregation—as, for instance, do minimum-lot-size regulations. Nonetheless, the court’s decision in the Inclusive Communities case certainly lays the groundwork for broader application of the doctrine of disparate impact.

Some media commentary anticipates the political consequences of a day when exclusionary zoning comes under fire directly. For instance, the New York Times’ Thomas B. Edsall speculated on whether the specter of more affordable housing would push wealthy, white suburbs “into the arms of the Republican Party.” Edsall focused on New York’s Westchester County, but Boulder similarly is wealthy, white, and suburban. CityLab followed up Edsall’s piece with musings on whether broader application of the FHA might likewise turn heretofore liberal cities more conservative.

On the other hand, fair-housing proponents could hope that the question might arise, in communities that (like Boulder) aspire to principles of fairness and equal opportunity in housing, whether the disparate impact of their zoning rules on minority groups are something they can countenance, irrespective of Supreme Court rulings. The question for these communities is: is it consistent with our values, and is it healthy for the city as a whole, that de facto segregation remains so firmly entrenched in our community?