Editor’s note: Throughout the summer we will run a serialized version of PLAN-Boulder County’s A Transportation Vision for Boulder. This is the introduction.

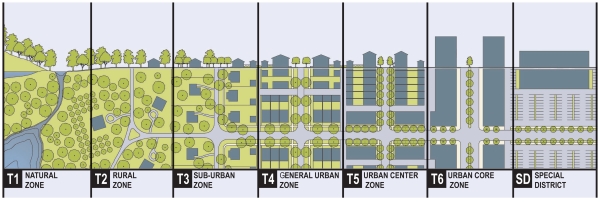

Many town planners, in recent years, have adopted the tactic of using a rural-to-urban transect for community design. Using this method, communities can equitably provide for the full range of lifestyle and travel choices. A community should provide for those who seek a walkable, compact lifestyle. It should also provide for the more dispersed, low-density lifestyle.

The rural-to-urban transect is a concept that acknowledges that individuals have a range of different lifestyles and forms of travel that they desire. Instead of having a community establish only one set of design regulations and one set of transportation objectives for new development in a community, it is more equitable that regulations and transportation designs be tailored to the full range of choices: walkable for a town center, drivable/bikeable for low-density neighborhoods, and rural/conservation for the periphery of a community.

Not only is this tailored approach much more fair than a one-size-fits-all approach, it is also more resilient: the future is likely to be quite different than today, particularly due to likely resource, financial, demographic, energy and climate changes. Creating a full set of community designs will lessen the impact of significant community shifts to news way of living and getting around, so changes will not be as painful and costly.

In addition, establishing a range of regulatory zones and transportation patterns is more sustainable, politically. Conventionally, the community must engage in endless, angry philosophical battles to determine the most acceptable one-size-fits-all lifestyle and travel preferences (which inevitably mean that the regulations and designs must be watered down to a mediocrity that no one likes—as a way to minimize objections). Instead, when lifestyle zones are established (urban, suburban, rural) and both land use regulations and transportation designs are calibrated differently for each lifestyle zone, political battles are minimized and the regulations and designs can be more pure.

There are at least three major transect zones (communities that adopt transect development regulations may have up to 8 zones). Each zone has lifestyle and travel design objectives that are calibrated to promote the lifestyle and travel in question. Design elements that undercut the objectives of a zone are called Transect Violations. The walkable zone strives for relatively compact, human-scaled, slower speed street traffic design. Light fixtures and fences are shorter. Buildings are taller and more likely to mix residences with retail or services. Alignments are more rectilinear, hardscapes typically are emphasized over greenscapes, and landscaping is more formal. Setbacks are smaller. Streets are more narrow and distances between homes and shops are relatively short. Car parking is more scarce and more expensive to use. Densities tend to be higher. In the walkable zone, “more is better.” That is, a walkable lifestyle tends to be higher quality when more housing, retail, services, and culture are added. The drivable/bikeable zone seeks to be more spacious, more private, and densely vegetated. Roads are wider and speeds are higher. Buildings are shorter and usually single-use. Car parking is more abundant and cheaper to use. Setbacks are larger, as are distances between homes and shops. Densities tend to be lower. In the drivable zone, “more is less.” That is, a drivable lifestyle tends to be lower in quality when more housing, retail, services, and culture are added. The rural conservation zone is focused on preservation and is more isolated. Landscaping is relatively naturalistic. Sidewalks and bus service tends to be absent. Speeds are relatively high. Open space, farming, and pasture tend to be abundant.

For Boulder, one might think of the walkable urban zone as Boulder downtown (the “town center”) or Boulder Junction, the drivable/bikable zone as our low density neighborhoods within the urban growth boundary (city limits), and the rural conservation zone as unincorporated Boulder County lands surrounding the city. Similar transects could be constructed for all the cities in Boulder County.

Unfortunately, in most American cities—including Boulder—the supply of walkable, compact housing is far short of demand for such housing (which substantially increases the cost). Conversely, across the nation, there is a larger supply of drivable, more dispersed housing than the demand for such housing (which was recently exemplified by the fact that suburban housing values in most of the nation suffered significantly during the housing crash of the late 2000s). Indeed, communities such as Boulder face a growing housing crisis in the future, as the so-called Millennial generation is less interested in the drivable suburban lifestyle than previous generations.

Considering the current focus on walkable urban development in Boulder, this paper devotes much discussion to what represents the transect zone most in need of improvements: the walkable, compact, existing and emerging town centers in Boulder.

Due to the current demand for this form of lifestyle, Boulder needs to provide substantially more walkable, compact housing in future years to create a balanced housing supply and to increase resilience. However, Boulder has worked hard to create vibrant town centers and to connect lower density areas through our network of frequent buses and Eco Passes, bike and pedestrian walkways, and abundant signed crosswalks and underpasses. This is partly why, for example, those who live and work in Boulder commute by bicycle at a rate 20 times the national average.

This paper, which is organized into four main sections (described below), will appear on the Blue Line in multiple, smaller parts.

Section 1 describes the economics of transportation. Healthy cities need clustering to promote exchange, yet oversized, high-speed roads disperse cities, which undermines exchange. This section describes motorist subsidies, affordability tactics, low-value car trips, efficient parking tactics, congestion and air emissions, and the problem of diminishing returns.

Section 2 describes how urban design shapes and is shaped by transportation. This section addresses the proper sizing of streets, blocks, and intersections, describes the significant problems associated with gigantism, and looks in detail at the merits of right-sizing streets. Also discussed are car speeds, design for safety, problems associated with one-way streets, and suburban sprawl.

Section 3 looks at regional car trips and how to effectively manage them. This section also proposes smart transportation and smart land use tactics.

Section 4 considers sustainable, green travel such as walking, transit, and bicycling. Presented here are effective ways to promote green travel. Concluding remarks address the important need to make people happy, not cars.

The mission of PLAN-Boulder County is to ensure environmental sustainability, promote far-sighted, innovative, and sustainable land use and growth patterns, preserve the area’s unique character and desirability, and reduce our carbon footprint and environmental impact.

PLAN-Boulder County envisions Boulder County as mostly rural with open land between cities and towns that support working farms on good agricultural land and provides for conservation of critical habitats for wildlife and native flora. Within Boulder and neighboring communities, urban boundaries limit sprawl and growth is directed to meet community goals of housing affordability, diversity of all kinds, environmental sustainability, neighborhood identity, and a high quality of life. PLAN-Boulder County further supports green building practices that minimize energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, PLAN-Boulder County supports a more balanced transportation system that actively promotes public transit, bicycle commuting, and pedestrian travel, and provides for smarter use of automobiles.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the various city and county organizations with which the authors are affiliated.

Dom Nozzi, principal author of this paper, is a member of the PLAN-Boulder County Board of Directors and the City of Boulder Transportation Advisory Board. Mr. Nozzi has a BA in environmental science from SUNY Plattsburgh and a Master’s in town planning from Florida State Univ. For 20 years, he was a senior planner for Gainesville, Forida and was also a growth rate control planner for Boulder. He has authored several land development regulations for Gainesville, has given over 90 transportation speeches nationwide, and has had several transportation essays published in newspapers and magazines. His books include Road to Ruin and The Car is the Enemy of the City. He is a certified Complete Streets Instructor providing Complete Streets instruction throughout the nation.

Pat Shanks, Jeff McWhirter, Alan Boles and Scott McCarey also contributed to this paper.