On Friday, December 6, 2013, Timothy Seastedt, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at CU, a fellow of the Arctic and Alpine Research Institute, and a member of the board of directors of the Wildlands Restoration Volunteers (WRV), suggested at a PLAN-Boulder County forum that wildlands managers should probably not try to restore them to the “historical community” that existed before man-made impacts caused degradation, but should aim to facilitate a “deliberately altered ecosystem.” Seastedt also described the organization and programs of WRV and outlined some of the possible effects of the 2013 flood.

Seastedt recounted that the WRV was founded by Ed Self in 1999, and that his goals included insuring that “no child [is] left inside” and reducing “nature deficit disorder.” WRV has offices in Boulder and Fort Collins, eight full-time staff members, three part-time staff members, and a yearly budget of over $900,000. In 2013 it completed more than 76 projects, using about 3,338 volunteers who donated about 43,000 hours. A total of 19,666 feet of trails were re-routed or restored, he said, and 11,485 trees and shrubs planted. He proudly disclosed that PLAN-Boulder County’s own Ray Bridge, who currently serves as PBC’s co-chair, had received WRV 2013 award for tool-manager of the year.

WRV specializes in providing volunteers to government agencies that lack the staff to recruit them, Seastedt declared. He also said that WRV is able to coordinate restoration projects on lands owned or controlled by different entities, including private owners.

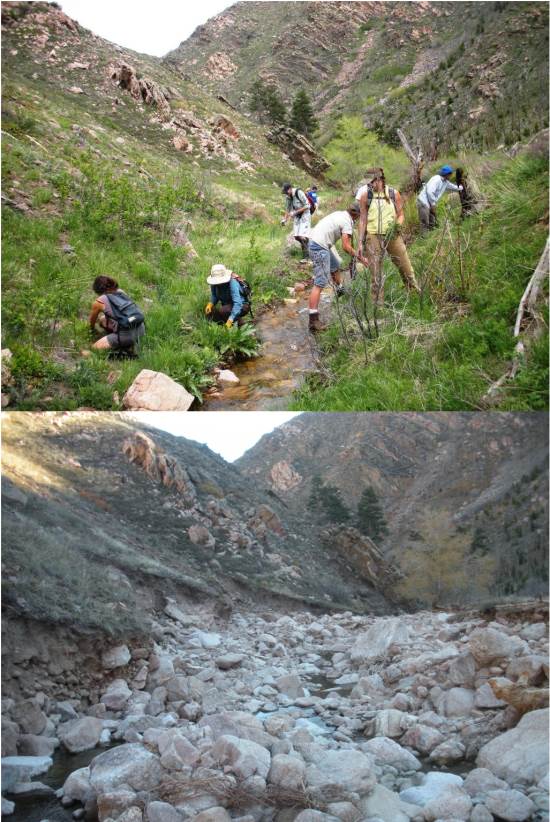

WRV volunteers removing invasive plants in a drainage (above) and the same view after the September flood (below). Photos courtesy Tim Seastedt.

Seastedt related that WRV has completed six projects precipitated by the 2013 flood, using 350 volunteers in Boulder, Lyons, Lafayette and Eldorado Canyon State Park. He also said that it had formed two coalitions, one to restore recreational infrastructure and waterways in Boulder County, and the other to restore the Big Thompson watershed.

Seastedt contended that wetlands and riparian zones are probably the most valuable areas on which to concentrate management efforts. They contribute vital “green water,” which evaporates into the sky, and “blue water,” which runs in the streams, to eco-systems. Ironically, Seastedt admitted that most of WRV’s volunteer time is spent building or repairing trails for human use, particularly since the 2013 flood. He said that “stakeholder demand” dictated the priorities.

Some old mining roads in the mountains were destroyed by the 2013 flood, Seastedt observed, and will not be restored. Their disappearance will reduce human traffic in wildlands to some degree. He also remarked that the 2013 flood may help wildlands managers to eradicate some invasive species.

Seastedt said that botanists are excited to study the effect on plant species of the extraordinary amount of water that fell in September, 2013. He observed that native grasses have been slowly diminishing in this region, while flower-producing plants have increased. Because temperatures had been warm before the 2013 flood, Seastedt theorized that almost every seed in the ground had germinated during the deluge or right afterwards. As well, most surface soils (where the seed bank rests) were leached of soluble nutrients. So seedlings must persist over winter with little nitrogen. He speculated that this nitrogen-poor environment may favor the native grasses.

Seastedt recounted that the traditional goal of wildlands restoration has been to re-establish the “historical community” that prevailed before humans altered the eco-system. However, he suggested that that objective should be re-considered. “Getting rid of what you don’t want under the new rules only facilitates additional changes,” he declared. However, he also asserted that “doing nothing allows for uncontrolled change caused by directional ‘drivers’ like fire suppression and atmospheric chemistry, or extreme, climate-related events, such as catastrophic flood and fire.” Instead, he advocated that the new ideal for wildlands managers should be a “deliberately altered eco-system.”