Editor’s note: This article was adapted by the author from a paper written for an urban planning course at Cornell

Driven by a localist philosophy of city planning, in 1958 a group of City of Boulder residents initiated an enduring shift in the city’s land use policy. Beginning with a conversation among University of Colorado professors, a vision for keeping Boulder small was formulated. Recruiting friends and neighbors, a coalition gathered that became the People’s League for Action Now, or PLAN-Boulder (later PLAN-Boulder County, or PBC). The initial goal was the implementation of a western growth boundary to the City of Boulder.

The start of PLAN-Boulder and the creation of the first growth barrier, called the Blue Line, were significant events as they catalyzed the creation of a 360-degree growth boundary around the city. Impeding westward development was the first step toward the creation of an official city policy of strategic land and easement purchases. Successful efforts to slow the process of city annexation were followed by an organized effort to prevent future residents, or other municipalities, from developing surrounding lands outside the city’s existing footprint. By the 1960s, PBC was a key player in a political campaign to create a comprehensive open space program. In 1967, city residents voted in favor of a sales tax increase to finance open space land acquisitions.

The city and county’s economy, social equity, and quality of life would not be as they are today if not for this self-imposed growth limitation. Organized into three sections, this essay explores the underpinnings of PBC’s actions and impact: the first section recounts a brief history of PBC as an organization and its historic context; the second section analyzes PBC’s strategy and principles relative to significant urban theories; and the third section assesses how PBC’s original operational theories have been made manifest today.

History

Organizing in the late 1950s, PBC’s electoral and political achievements represent early citizen-driven local control. In the post-World War II period, consumption and the American suburb were burgeoning and the City of Boulder experienced rapid growth. It was this expansion that brought PBC’s members together. A particular driving force bringing the organization’s members together was the City of Boulder permitting the construction and incorporation of new subdivisions in the foothills above town.

Activists led by University of Colorado professors and affiliates Bob McKelvey, Al Bartlett, and others organized a political campaign for a city charter amendment to impede the growth occurring on the mountain slope just above homes in the University Hill neighborhood. Part of their original concern was that the city needed to enforce the police power to not allow building that would trigger landslides into the homes below. But arguably more important was a concern for aesthetics.

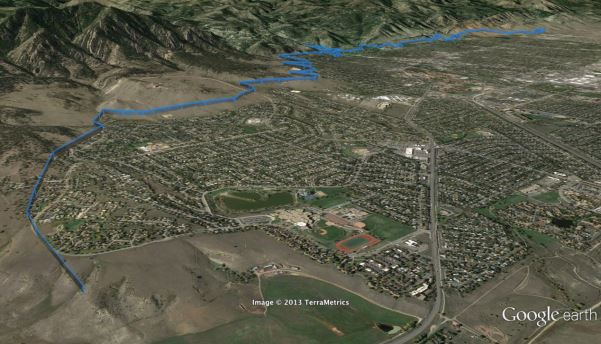

The amendment these PBC forerunners proposed was a creative solution to their desired end of seeing no more construction on the foothills visible above town. The charter amendment stipulated the city would not provide water to residences above 5,750 feet. The city’s base elevation is 5,430 feet. McKelvey stated in a 2002 interview, “This water situation was our secret to control things” (Oral History). After collecting signatures to trigger a referendum, the amendment was put on a July ballot. The Blue Line, as it was called, was approved with a vote of 2,735 in favor and 852 against.

Approximate Blue Line at an elevation of 5,750 feet along the city’s western edge (click to enlarge)

After the success of the Blue Line political action campaign, the amendment volunteers gathered to solidify their political action identity as PLAN-Boulder, which later became PLAN-Boulder County. Immediately, PBC rallied behind politically aligned City Council candidates in the fall election. They hosted candidate forums and publicized candidate endorsements in the fall election. A newsletter released by the group at the time stated, “The Problems we face, and they are nationwide, are new…they demand new and imaginative solutions and immediate action.” The underlying problems being urban sprawl, keeping “attractive” areas green and open, and the need for “forceful use of annexation policies to insure that newly developed areas more nearly pay their way” (Robertson). This started PBC as an anti-growth watchdog group that endures in Boulder politics to present day.

PBC’s Actions through an Urban Theory Lens

Attachment to place and environmental context were central to PBC’s mission with the Blue Line. Growth limits shifted land control power to favor existing landowners and already developed parcels. This essay uses three urban theory frameworks to understand PBC’s actions: (1) There is an acknowledgement that cities operate like Molotch’s Growth Machine; PBC’s actions characterize what in 1976 Molotch termed a countercoalition to the growth machine. (2) PBC’s actions reflect an early understanding of urban ecology and the power, health, and wealth that come with control over a city’s ecological domain. And, (3) PBC’s actions removed the City of Boulder’s lands from the capricious fluctuations of the neoliberal economy; thereby, Boulder was insulated from many negative impacts of the real estate markets cyclical booms and busts.

The Countercoalition to the Growth Machine:

“The city is, for those who count, a growth machine,” writes Molotch. This “growth” is manifested as a “constantly rising urban-area population.” A ballooning population is a symptom of the chain reaction process of “…expansion of basic industries followed by an expanded labor force, a rising scale of retail and wholesale commerce… and increasingly intensive land development, higher population density, and increased levels of financial activity.” In the Growth Machine, while political disagreement may exist over specific social issues, the one universal value is that growth is good. Because of this logic, in many communities there is little contention when local officials promote pro-growth strategies.

At its founding, Boulder operated like other communities. Prospectors settled Boulder in 1858, and from that time through the 1940s the city’s population growth was moderate. During this slow growth period, there was a desire to kick-start the Growth Machine. In 1872, an immigration society was formed for exactly the purpose of publicizing the area to attract more population. In 1877, the University of Colorado (CU) opened, providing population stability. But beyond the university population, the growth rate of the rest of the population eked upward only as mineral discoveries were made in the surrounding natural areas (Public facilities plan).

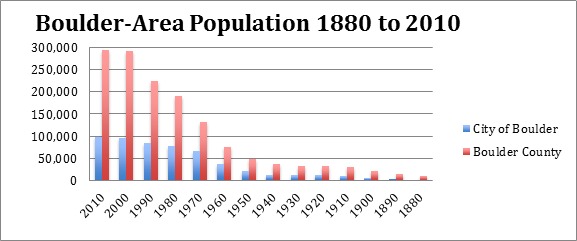

Major population growth occurred from 1940 to 1957. In part this was due to CU’s student population doubling with the return of WWII veterans. The population grew from 13,000 people to 32,000, or 146%, during the period (see population growth chart below) (Plantico). City planning officials wrote in a 1963 capital investment report, “Rapid growth and significant change characterized the years beginning with 1950…development had for the past half century lain dormant but suddenly, as though unable to be longer restrained, burst forth in dynamic growth.”

Beyond student expansion, further explanations for the growth were a new turnpike connecting Boulder to Denver and the installation of a federal laboratory. Both events contributed to the subsequent arrival of Dow Chemical Company, Ball Research Group, and Beech Aircraft. “People came. Building activity increased. Traffic increased. The economic base expanded” (Public facilities plan). Triumphantly, the 1963 report proclaims, “The pattern of sporadic growth, centered around isolated incidents giving temporary impetus to the economy of Boulder, is something of the past.” The Growth Machine was operating at full throttle!

Up until the early 1950s, city residents were a welcoming “we”—desperate to attract additional population in order to ensure economic survival. After the rapid population expansion and the rise of PBC, Boulder became a “we” apart from the rest of the Front Range (Molotch). According to Molotch, the Growth Machine only operates in the interest of the broad community up to a point. Beyond that point the marginal advantages of growth accrue only to a few business people and developers. In Boulder, PBC’s pursuit of limited growth shifted the advantages to local voters instead.

In 1971, National Bureau of Standards physicist Eric Johnson authored a report titled “Is Population Growth Good For Boulder Citizens?” Fifteen members of a citizens’ group called Boulder Zero Population Growth supported the research. In a panicked tone, after a hundred plus pages of bar charts showing statistics from 1960 to 1968 and changes in per capita costs of various city services, Johnson’s group made a strong anti-growth assertion. Their two conclusions were: (1) “…population growth without true reason is likely to have no true value. Current population growth in Boulder is population growth without a true reason”; and (2) “…those who advocate population growth must bear the burden of proof when they assert that population growth is good for the ordinary citizens of Boulder. We were unable to find such proof. As far as we can tell we have enough people in this area. There appears to be no further gain to be had by bringing more people into the city. This includes all entities in the city—private, corporate, college, and governmental” (Johnson). Although the grassroots group Boulder Zero Population Growth was not directly linked to PBC, their publication represents the ethos of the time in Boulder.

PBC’s emergence was a response to a cascade of population growth. Although driven by strong feelings, intuitively, PBC members sensed what would later be proven, “growth often costs existing residents more money… A study of Santa Barbara, California, demonstrated that additional population growth would require higher property taxes, as well as higher utility costs… Similar results on the costs of growth have been obtained in studies of Boulder, Colorado…”(Molotch). Beyond monetary considerations, an environmental science justification espoused by PBC was the limit of the area’s environmental carrying capacity. If the city got too large, “the natural cleansing capacities of the environment” would be overwhelmed (Molotch).

The Blue Line initiative inspired a challenge to the Growth Machine dogma that city growth equates to improvements in quality of life. In denying the precept of growth being good, PBC recognized that, “land, the basic stuff of place, is a market commodity providing wealth and power” (Molotch). By taking control of the land surrounding Boulder, wealth and power was shared with all existing landowners in the city. Once the value of open land became a shared wealth, in the way growth for most communities is common virtue, anti-growth became Boulderites’ shared value.

Early Acknowledgement of Ecological Domain

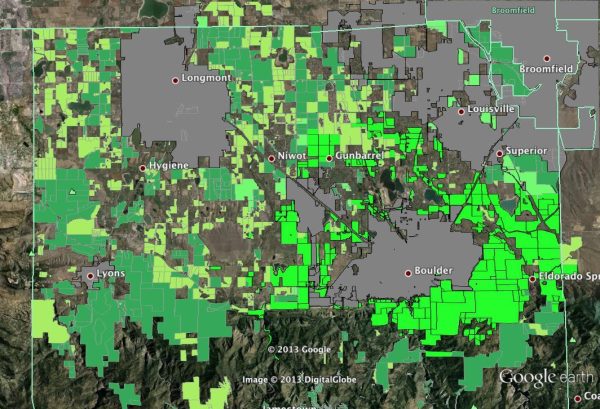

The Blue Line of 1959 set the stage for Boulder’s Open Space Program of 1967. In turn, the city program was followed by Boulder County acquiring its first open space in 1973. The combined development easements and land holdings of Boulder County and the City of Boulder make it clear there is limited developable land left outside of urban areas in the flat portion of the county.

Of significance is that Boulder County land easements (shown in light green in the next figure) and open space (bright green for City of Boulder and dark green for Boulder County) are concentrated around city footprints (in grey). The large gaps where there is neither City of Boulder nor Boulder County holdings are primarily far from existing urban centers. For the City of Boulder especially, the result of controlling the lands immediately surrounding the urban boundary is that land use ordinances are more impactful. Land use zoning policies, such as broad impediments to additional large box retailers, and not permitting additional drive-through restaurants are more effective as there is little possibility of a retailer setting up just outside city limits. Open space and land easements empower the city to have greater economic control of its proximate domain.

Control of an ecological scale beyond the traditional urban and jurisdictional boundaries translates to power. Swyngedouw and Heynen contend that for communities there is a “continuous reorganization of spatial scales” and this “is an integral part of social strategies to combat and defend control over limited resources and/or a struggle for empowerment.” By asserting control over a scale beyond itself, the City of Boulder made distance and scenic beauty into essential city resources. Business districts within the city limits, containing many local businesses, have less competition from retailers in neighboring communities. Consumers who reside within Boulder make purchases in town because there is value in not having to travel to the next town to make purchases, even when shopping may be cheaper in other localities. The result is sales tax dollars stay in the city and thereby add to community’s local wealth.

The economic buffer of PBC’s land use vision may be understood through the lens of David Harvey’s theory that there is no logic in separating urbanity and nature. The Blue Line merged the policies of natural preservation and economic development. Though counterintuitive, while the Blue Line was a limitation on the city’s physical build out, with its implementation, PBC and Boulder’s general political discourse began viewing urban interests as going beyond where city streets ended. Equally as significant as controlling where city infrastructure went was having a say over where street and sewer infrastructure did not go. In an expansion of the city’s ecological scale, by making the surrounding “nature” a part of the City of Boulder, the more open space that was acquired, the less susceptible the community was to shifts in the spatial balance. Be these economic shifts or demographic shifts.

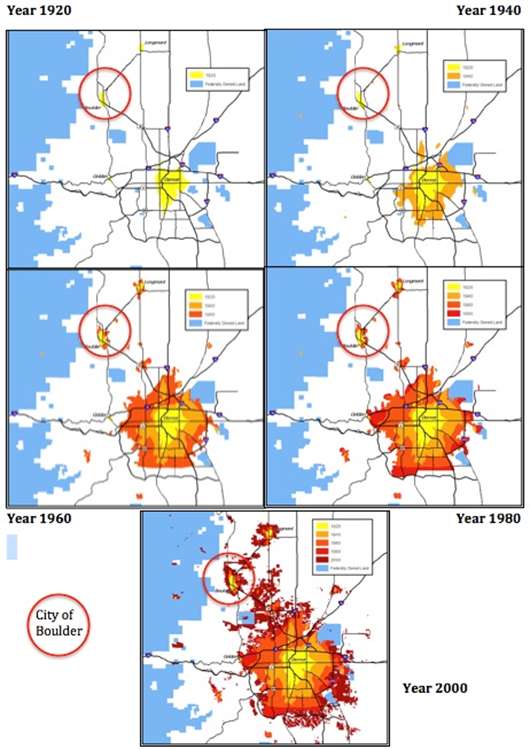

At the regional level, in 1963, Boulder is described by city planning staff as having “most of the characteristics of a ‘central city,’ in that it is largely a self-sufficient city, and is, to a degree economically, culturally and socially independent. Boulder is not, however, the major economic and social center of an urban area, and thus, it does have this characteristic of a satellite city” (1963 Capital Plan). As growth occurred in communities across the Front Range, it was increasingly apparent in the Denver metropolitan area that municipalities’ boundaries would run up against one another. But for the City of Boulder, open space buffers assured it a status as a place physically apart. Through growth limits and taking control of the reorganization of spatial scales, Boulder impeded the process of becoming a satellite suburb of Denver. The following graphic courtesy of the City of Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks department shows the growth of the Denver-Metro area from 1920 to 2000:

Neoliberalism’s Treatment of Land During Booms and Busts

A point of controversy around the Blue Line was whether it really needed to be in the City Charter. When it was voted on in the summer of 1959, some community members outside of the PBC fold contended it was best to trust elected officials to maintain a Blue Line as a norm rather than a law. Such a norm would either be maintained until elected officials broke faith, or when voters no longer wanted a barrier to growth. If trust or public will changed, the appropriate mechanism would be to un-elect public officials. The PBC stance voiced by Al Bartlett was, “if [the Blue Line] wasn’t in the City Charter it would have been violated a million times and [the growth boundary] would be gone by now” (Oral History). The charter amendment was a proactive and binding land policy for future generations. As a consequence, the Blue Line defined the tone of land use politics for decades to come.

A further implication of Bartlett’s statement is that were the barrier not a permanent feature of the city’s foundational documents, elected politicians would not have been strong enough to resist market pressures. Ultimately, a norm would have been overrun and building above the Blue Line permitted. Since the barrier’s enactment, arguments that government should make decisions more inline with the market have become commonplace. Increasingly popular since the end of WWII is neoliberalization, “a hypermarketization style of governance that denigrates collective consumption and institutions. It is also an ideological fetishization of pure, perfect markets as superior allocative mechanisms for the distribution of public resources” (Weber). PBC’s actions flatly rejected this “best” form of resource allocation, and because it was in the Charter, the Blue Line instigated a limited growth path for the future growth of the city.

By institutionalizing a counter-market land use policy, PBC provided a strong community mandate for City Council members to further limit population growth. By no means did the land use limitation operate in the entire community’s interest, especially for those yet to arrive. However it did operate in the interest of those already a part of the community. A 1966 report released by the city’s Department of Planning and Development reflected how PBC’s proactive stance was built into official city policy. The report states, “From 1950 on, planning in the city and the county was committed to the idea that the city’s fringe area was an integral part of the city itself” (City of Boulder). By embracing control of its fringe, the city was free to focus resources on the existing urban footprint.

This rejection of a neoliberal form of local governance allowed the existing parts of the City of Boulder to avoid the fate of obsolescence and the pain of market induced creative destruction. Beyond government investment, constructing a growth barrier to the west brought greater alignment of “the temporal horizons of investors, developers, and residents,” which “rarely coincide” (Weber). Reflective of this unity was the fact that Boulder was “a highly developed city, with only an estimated 16 percent of its land vacant in mid-1962 as compared with vacant land amounting to nearly 23 percent of the land in satellite cities and about 50 percent of the land in central cities” (56). Infill and renewal became increasingly the only options for developers doing business in the city.

Legacy of PBC’s Actions In Practice

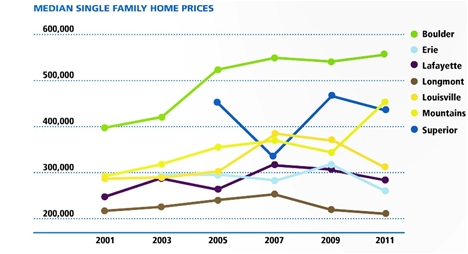

Over the last half-century, the ramifications of PBC’s efforts to impede growth resulted in development investment occurring within close proximity of the city’s 1960 footprint. Most “green pasture” development occurred outside the green belt and increasingly outside the county. Advantages of keeping the physical size of the city small are elevated bicycle and pedestrian commuter rates (close to 15 percent of the commuter population), a robustly funded city Health and Human Services Department, and a thriving downtown outdoor pedestrian mall. Limiting the space for new housing tracts helped Boulder County’s existing communities to not be saddled with the detritus of abandoned real estate during the financial crisis and housing bubble of 2008 (see graph below). Strict land use regulations protected Boulder from Weber’s characterization of neoliberalism’s investment and disinvestment cycle.

A financialization of Boulder’s economy has occurred in part contributing to elevated property prices.

Conclusion

For many of PBC’s members their personal identity is tied to being residents of the City of Boulder. When the city’s physical form or quality of life are derided by voices from outside, PBC members take personal insult. There is a collective sense among those residing in the city limits that they hold similar values and are on a municipal team. There is a sense that the Boulder municipal team exists in persistent struggle among area cities to remain distinctive and thriving.

While this zero-sum view may be challenged as shortsighted, there is no denying that Boulder’s central business district has thrived while other communities’ have not. At any given time there is a limited number of consumer dollars available to be spent in small Front Range communities. Land use limits provide Boulder a competitive edge in the rapid process where “Capital circulates through the built environment in a dynamic and erratic fashion” (Weber). The circulation of capital often results in “the built environment [being] junked, abandoned, destroyed, and selectively reconstructed” (Weber). Since the 1960s, Boulder largely avoided the fate of being “junked” through restrictive land use that increased the value of already incorporated land. Today’s PBC members ask why should Boulder change its land use agenda when it has created a high quality of life for those who reside here?

There is an argument to be made that though the city’s land use policies make it an exclusive enclave, the city is worth more to the Rocky Mountain region in its present form than if its land use practices were the same as everywhere else in the Denver Metro-Area. On net, the city generates employment due to its land use. For those inside the Boulder bubble, it is clear that in the struggle “between use and exchange values, between those with emotional attachments to place and those without such attachments” the PBC protectionist, preservationist mindset rules (Weber).

In Boulder, there is a strong allegiance to place. The result is long-term community buy-in, which translates to stability. In the context of global cities and fast moving capital, why should anywhere so far from the economic cores be thriving? By elevating quality of life above growth, and turning nature into a luxury good (Glaeser, 2011), Boulder, Colorado, made a name for itself.

Citations

Bartlett, A. A., Gerstle, K., Wright, R. M., & Errickson, G. (2002). Oral history interview with Al Bartlett, Kurt Gerstle and Ruth Wright. (Maria Rogers oral history collection.)

Boulder (Colo.), Boulder County (Colo.), Boulder Valley School District Re 2., & Trafton Bean and Associates. (1958). Guide for growth, Boulder, Colorado. Boulder, Colorado.

Boulder (Colo.)., & Goodwin, E. F. (1966). The growth of a community: Planning and development: City of Boulder, 1859-1966. Boulder, Colo: City Planning Office.

Glaeser, E. L. (2011). Triumph of the city: How our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier, and happier. New York: Penguin Press.

Harvey, D. (1997). Contested Cities: Social Process and Spatial Form. In LeGates, R.T and Stout, F. (eds.), The City Reader (pp.225-232). New York, NY: Routledge Reading on Bb

Johnson, E. G., Borders, R., & Boulder Zero Population Growth. (1971). Is population growth good for Boulder citizens?. Boulder, Colo: Boulder Zero Population Growth.

Molotch, Harvey (1976). The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place. The American Journal of Sociology, 82 (2), 309-332. http://staff.ycp.edu/~sjacob/SOC340/Supplemental%20Readings/The%20City%20as%20a %20Growth%20Machine.pdf

Patton, Mike. “Urban Growth: Denver-Boulder Metro Area 1920-2000”. Boulder, CO: City of Boulder Open Space and Mountain Parks Dept.

Plantico, Cailyn. (2008). “ The Blue Line Amendment and Enchanted Mesa Purchase: Setting the Stage for Boulder’s Open Space Program.” City of Boulder, Colorado, Open Space & Mountain Parks Program. http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/files/openspace/pdf_education/e_mesa_purchase.pdf (available at http://www.boulderblueline.org/pdfs/e_mesa_purchase.pdf)

Public facilities plan and capital improvements program, 1963-1985, Boulder, Colorado. (1963). Boulder, Colo: s.n..

Robertson, Josephine. (1989). Highlights of PLAN-Boulder County 1959-1987. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: PLAN-Boulder County.

Roger, M. & Taffet, M., (2011). Boulder County TRENDS Report. The Community Foundation Serving Boulder County. http://www.commfound.org/trendsmagazine

Swyngedouw, Erik and Heynen, Nikolas C. (2003). Urban Political Ecology, Justice and the Politics of Scale. Antipode. 35 (5). pp. 898 – 918

Weber, Rachel (2002). Extracting Value from the City: Neoliberalism and Urban Redevelopment. Antipode. 34 (3), 519-540.

http://www.worldcat.org/title/extracting-value-from-the-city-neoliberalism-and-urban-redevelopment/oclc/360328209

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)

(5 votes, average: 4.00 out of 5)