At a PLAN-Boulder County forum on Friday, February 8, about the wisdom of the Transportation Maintenance Fee (TMF) proposed by the City of Boulder’s staff, panelist Steve Pomerance argued that it is seriously misconceived by failing to mitigate the expected increase in vehicle miles travelled in the city, while the other two panelists, Chris Hagelin and Sue Prant, claimed that it is badly needed to reverse the decline in the purchasing power of current maintenance revenues for city roads and streets and perhaps to pay for other transportation initiatives.

Panelist Chris Hagelin is the senior transportation planner for the City of Boulder’s transportation division. Panelist Steve Pomerance is a former Boulder City Council member, former PLAN-Boulder board member, and free lance policy analyst. Panelist Sue Prant is executive director of Community Cycles, which supports the proposed TMF.

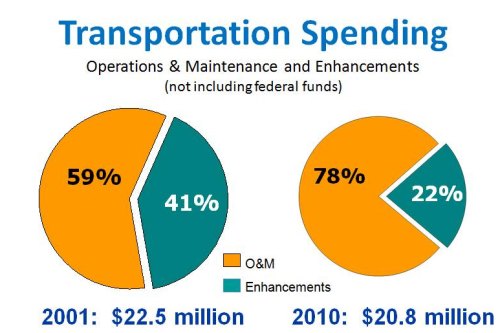

Hagelin explained that city transportation spending declined from $22.5 million (not including federal contributions) in 2001, 59 percent of which was for operations and maintenance and 41 percent for enhancements, to $20.8 million in 2010, 78 percent of which was for operations and maintenance and 22 percent for enhancements. More significant, he stated, was a 38 percent decline in purchasing power by the transportation division since 2002. This has led to a $3.2 million, unfunded need for transportation operations and maintenance, he asserted. Hagelin claimed that, if streets deteriorate below a certain condition, they need to be re-constructed, rather than re-paved, which is a much more expensive operation. But he admitted that the current condition of Boulder’s streets is far superior to the level that would require re-construction.

Hagelin recounted that the City’s Blue Ribbon Commissions I and II had called for more diversity in funding sources for transportation (which is now mostly paid for by a dedicated sales and use tax). He said that the 2009 Transportation Funding Report recommended a TMF as the most viable finance mechanism for transportation operations and maintenance. This approach was considered at City Council study sessions in 2010 and 2012. A consultant was engaged in 2011 to design a TMF, and the city’s TMF task force examined the subject in 2012. The City’s Transportation Advisory Board has endorsed a TMF, Hagelin stated. The City Council is expected to decide this spring whether to adopt a TMF or to place a TMF or a similar transportation maintenance tax on the ballot next November.

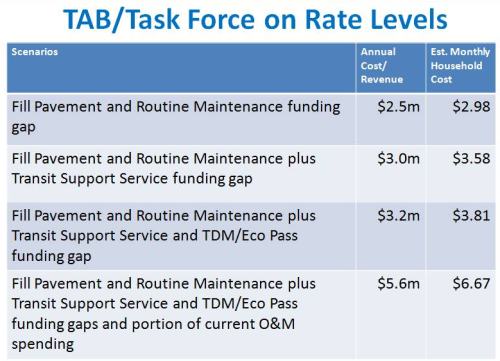

Four TMF scenarios are currently proposed:

Hagelin said that the rates would be based on land use and vehicle trip generation data from the Institute of Transportation Engineers and are intended to roughly approximate the burden that the users of different types of property impose on city streets. Rates would vary for multi-family attached, single-family attached, and single-family detached housing. Rates for commercial and industrial properties would be much higher than for residential, with commercial and retail uses paying the highest rate and warehouses the lowest.

Hagelin pointed out that the TMF could be charged as part of customers’ water and sewer utility bills and, thus, would be rather inexpensive to administer. He observed that it would be a stable and predictable funding source, that it could be indexed to increases in construction costs, and that it could include incentives and rebates. He also noted that such a fee could be legally imposed upon other governmental entities within the city, such as the University of Colorado and the federal labs.

Hagelin remarked that the City Council has left open the possibility of raising additional transportation revenues from a tax, rather than a fee. Such a tax, he cautioned, could not be applied to other government entities and could not be adjusted as costs increased. He said that the city would collect about 20 percent less revenue from a tax than from a fee that incorporated the same rates.

Pomerance, while readily acknowledging the need for more city transportation revenues, contended that a TMF would address the wrong problem. He pointed out that the city’s Department of Planning and Community Development projects that more than 60,000 jobs will be added to the workforce when the city reaches “reasonable build-out.” That employment increase will result in an increase of tens of thousands of cars on city streets, unless steps are adopted to limit it. He pointed out that the city’s streets are already nearing capacity and that even a small increase in traffic will cause a large increase in congestion.

He urged that this problem be addressed now, before it becomes a crisis, and that the way to do it is primarily through a parking fee—local governments in Colorado being prohibited from charging gasoline taxes or tolls. He extolled Stanford University as a successful example of the use of parking fees. He said when Stanford started to substantially increase the size of its campus facilities in 2000, prodded by Santa Clara County, it boosted on-campus parking fees from $300 to $800 a year, provided free transit passes and monetary incentives not to drive, and imposed capital charges on new development for needed infrastructure and transportation mitigation measures. He said that, as a result, single occupancy vehicle rates plummeted from 64 percent to 39 percent for all university commuters between 2002 and 2011, peak hour trips were reduced (even with an increased campus population), parking demand was reduced by 13 percent, and CalTrain use more than doubled.

Pomerance declared that the transportation revenue collected by a city parking fee would closely reflect actual usage of city streets. If the city charged on the basis of actual usage, he asserted, then people’s payments would correlate to the costs they create and they would make more intelligent choices. In contrast, he pointed out that a TMF would unfairly and inefficiently burden resident drivers much more heavily than non-resident drivers. He noted that the city’s water rates are intended to charge customers for both capital and operations and maintenance costs and asked why transportation charges should not be designed similarly.

Pomerance contended that a parking fee, in addition to raising needed revenue, could be an effective disincentive to driving a single-occupancy vehicle. He related that when gasoline prices rose from $3 to $4 a gallon, costing the average driver about $500 more a year, vehicle miles travelled decreased. He outlined a scenario, based on a city parking fee of $2 a day, under which $25 million a year would be initially collected and the effect on vehicle miles travelled would be about the same as a $1 increase in gasoline prices. He suggested that the parking fee might replace the $16 million currently raised by the city’s transportation sales and use tax, as well as the funds the TMF is projected to raise, and also perhaps at least partially pay for free RTD bus service.

Critical to the implementation of a city parking fee would be license plate scanning and recognition (LPR) technology, which, Pomerance said, Stanford has relied upon for its parking fee program. He reported that in one day he had contacted several vendors of LPR technology and had been assured that their systems are now very fast and effective. Payment could be by the web and smart phones, and residents, employees, and shoppers could be charged differently, he suggested. On-street parking in employment areas might be split into permit and metered parking, he stated, and retail areas might use LPR to charge a parking fee that would differentiate between employees, shoppers and students.

Pomerance readily conceded that his parking proposal is preliminary in nature and would require much more development before it could be actually put into practice. But he criticized the city for fixating on the TMF proposal to the exclusion of alternatives and pleaded for the city staff to devote even a fraction of the resources it has used to analyze the TMF to analyzing a city parking fee.

Pomerance also said that Fort Collins, the first city in Colorado to adopt a TMF, had dropped it and imposed instead a requirement that new development pay to mitigate all traffic increases that it would otherwise cause. He asked for Boulder to follow the lead of Fort Collins in this regard.

Hagelin claimed that the parking program of the Central Area General Improvement District (CAGID) in downtown Boulder closely resembled Stanford’s efforts and that Pomerance seemed to be asking for more such districts to be established around the city. Hagelin and Pomerance agreed that east Boulder, with its relatively large industrial areas, would be the most difficult part of the city in which to change the current parking scheme.

Hagelin questioned how much a parking fee might cost to administer. He said that he had discovered from work on the parking systems at Boulder Junction that LPR technology is very expensive. Hagelin also asserted that the city staff plans to study the city’s parking system in the near future after the TMF proposal is resolved one way or another.

Hagelin commented that changes to parking fees usually provoke widespread political opposition. Pomerance responded by asserting that elimination of the current transportation sales and use tax—as he suggested—might soften resistance.

Prant emphasized the urgency of the need for more transportation revenues and remarked that all current modes of municipal transportation—foot, bicycle, bus, and single-occupancy vehicle—depend on adequate streets and sidewalks. She claimed that now is the time to adopt the TMF and expressed fear that consideration of the proposed parking fee would needlessly delay it. “The perfect should not be the enemy of the good,” she declared. She also pointed out that the amount of a TMF for single-family, detached residences (the most heavily charged residential category)—somewhere between $35 and $80 a year—would be modest.