At a PLAN-Boulder County forum on February 24, 2012, former Boulder City Council member and leading civic figure DeAnne Butterfield depicted the scope of Colorado’s long-term, fiscal, structural deficit and outlined some possible remedies. Audience members Steve Pomerance and Bob Yuhnke independently suggested innovative ways to significantly narrow — or perhaps even eliminate — the gap.

The facts and figures which Butterfield presented were assembled by the Colorado Nonprofit Association, along with the Bell Policy Center, as part of an effort to stimulate public awareness of the state’s daunting fiscal challenge.

Butterfield observed that the costs to maintain public services exceed the revenues to pay for them in a state which already provides a relatively low level of such services and imposes relatively low taxes. Due to tax cuts under the administration of former Governor Bill Owens, only about 3½ cents of every dollar subject to sales and use tax ends up in the state’s general fund — in contrast to 5 cents before 1999. The income tax rate was also decreased under Owens.

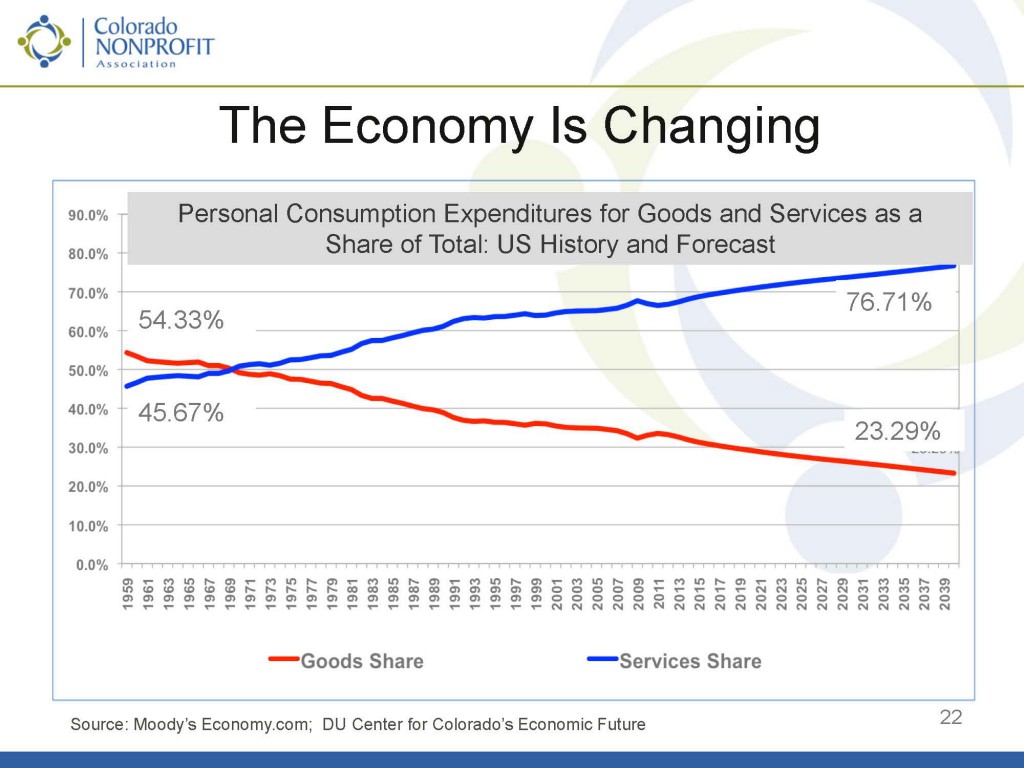

The economy has changed in Colorado and the rest of the U.S. so that the percentage of personal consumption expenditures disbursed for goods, which are generally subject to sales and use tax, has dropped from 54 percent in 1959 to about 33 percent today, while the percentage disbursed for services, which are not subject to sales and use tax in Colorado, has increased from 46 percent to about 67 percent. (These trends are projected to lower the goods percentage to 23 percent and raise the services percentage to 77 percent by 2039.) Inflation has reduced the purchasing power of Colorado’s general fund by 11 percent since 2001.

The major obligations of the general fund are Medicaid, corrections, and K-12 education — the “Big 3.” Under current circumstances, by 2017-18, 90 percent of general fund revenues, and by 2024-25, 100 percent of the general fund revenues, will be spent on the Big 3. Other state services, such as higher education, agricultural support, public health and environment, courts, and public safety, will have to be eliminated or funded through some other means.

Medicaid costs have been growing 1.7 times faster than revenues. An aging population now accounts for 27.2 percent of the total Medicaid expenses, up from 7.7 percent initially. (The aging population also depresses tax revenues, since people over 65 spend substantially less on goods than do people between 25 and 65 in age). The state’s Medicaid caseload has increased 60 percent since 2007, and health care costs have grown 40 percent over the past decade.

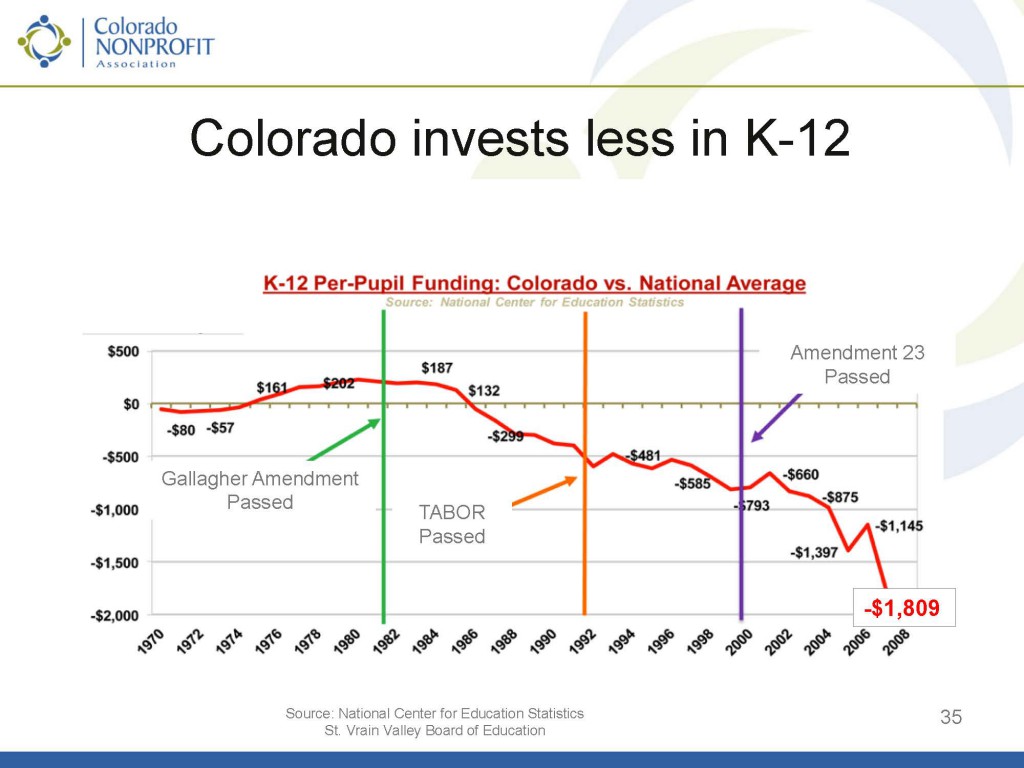

The state’s share of funding of K-12 education has increased from 35 percent in 1993 to 65 percent in 2010, while the average school district’s levy has dropped from 40 mills to 27 mills. The state’s share will peak at more than 70 percent by 2024-25.

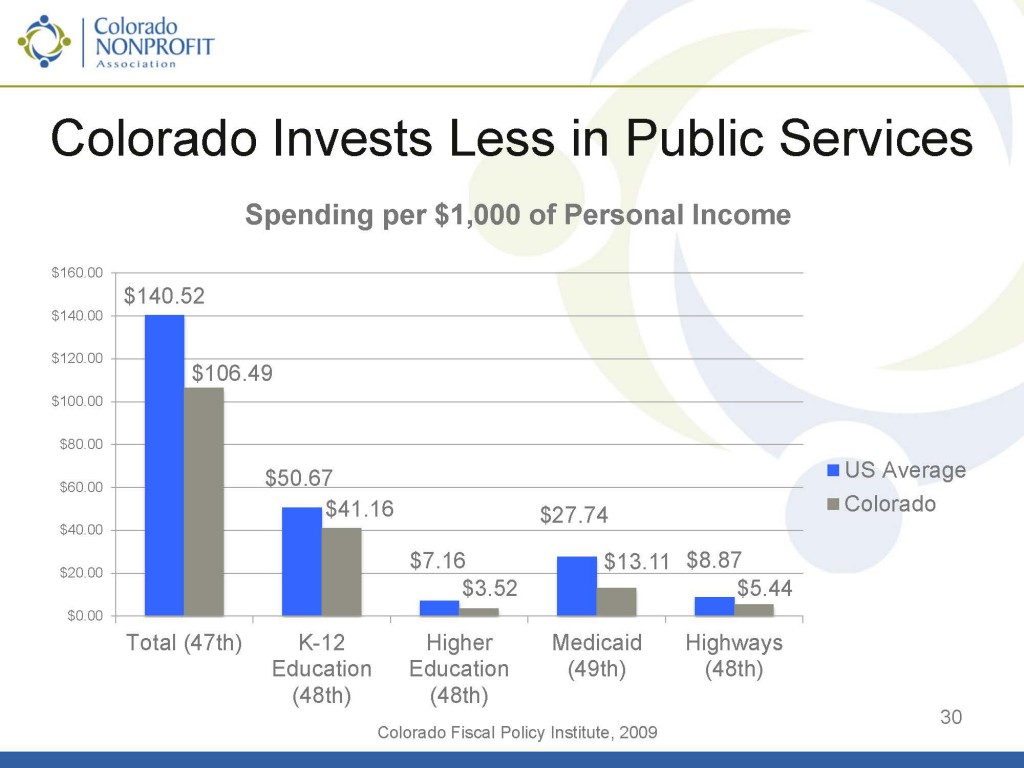

Colorado’s tax burden is relatively very low. Compared to other states, we rank 39th in combined state and local taxes and 49th in state taxes as a percentage of income; and our state sales tax rate is the lowest of the states which impose sales taxes (two do not).

Colorado’s public spending is also relatively very low. Compared to other states, we rank 45th in total state spending , 32nd in K-12 spending per student (and 48th as a percentage of income), 48th in higher education spending per $1,000 of personal income, 49th in Medicaid spending per $1,000 of personal income, and 48th in highway spending.

State expenditures on services outside the Big 3 have declined dramatically. Higher education funding as a percentage of total state funds has decreased from 21.1 percent in 1979-80 to 6.4 percent in 2009-10. General fund support to state parks dropped 60 percent in 2010 and is currently proposed to be zero. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment programs not funded by fees, such as carbon reduction, public health, and ozone standards, are being considered for discontinuation. According to the Colorado Department of Transportation, 7 percent of the state’s roads and bridges are in poor condition, 50 percent are in good or fair condition, and 128 bridges will be deemed unsafe in the next five years.

Butterfield asserted that the possible responses to the state’s fiscal, structural deficit are: (1) make no policy changes, in which event funding for K-12 education would be cut 19 percent for 13 of the next 14 years and the non-Big 3 services would be cut by 90 percent after 2017-18; (2) permanently reduce services; or (3) change the state’s tax code.

She claimed that the possibilities under the second option include:

- reducing eligibility levels for Medicaid, eliminating some coverage for low-income adults and increasing fees

- converting Medicaid to a public system resembling health savings accounts

- shortening school days for younger students

- reducing prison time for non-violent offenders

- redirecting funds from Great Outdoors Colorado to education

- imposing tolls on public roads

Butterfield also mentioned the following possible changes to the state’s tax code:

- including services in the sales tax base

- a statewide mill levy for schools

- restoration of the four graduated income tax brackets

- restoration of income and sales tax rates to the 1999 level

Butterfield remarked that the public is highly ambivalent about more taxes and fewer state services. In polls, 54 percent of voters declared that they would pay more for good schools, and 67 to 80 percent opposed any cuts to higher education, K-12 education, health care, and roads and transportation. But 50-67 percent opposed any revenue increases, and Proposition 103, which would have modestly raised sales and use taxes and income taxes to prior levels for a period of five years to fund K-12 education, was defeated last fall statewide by a margin of 64 to 36 percent.

After Butterfield’s presentation, Steve Pomerance proposed transportation and educational impact fees on new development as ways to fully fund the costs of adequate bridges, roads, and transit systems and pay for new schools for K-12 students. He claimed that $2 billion a year could be generated by a transportation fee and $1 billion by an education fee, and he distributed materials explaining his plan in some detail. He noted that state law does not require that impact fees be approved by the electorate.

Bob Yuhnke suggested that a higher severance tax be imposed by the state on oil and gas and minerals extraction and deposited in a trust fund. He suggested that the income from the fund be used to pay for education and/or other state services. He commented that Alaska has already created such a fund, and he likened it to the fund which was established by the Colorado constitution to pay partially for education through the sale of certain public lands and disbursement of the income on the proceeds.

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)

(3 votes, average: 3.67 out of 5)