2011 has thus far passed largely unmarked as the 50th anniversary of the publication of Jane Jacobs’ influential book on urban planning, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In 1961, the book was as close to a blockbuster as the topic of planning has ever seen. Today, while it is still widely read, some of its focus has become dated as planners have shifted much of their attention from problems of urban decay and flight to the suburbs to longer-term questions of sustainability, particularly in the context of climate change, global resource depletion, and the possibility of extended economic stagnation. Moreover, Jacobs is clear and unapologetic in focusing on the biggest American cities: New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and so on. Yet the book retains its relevance today, despite these changed priorities, and that relevance extends to urban design in Boulder, a place Jacobs would surely not regard as a city.

To understand Jacobs’ book, you have to understand the Modernist, anti-urban planning movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries; and to understand these movements, you have to understand conditions in large cities in Europe and America at the time, particularly in London and New York. Tenements in the cities were achingly overcrowded; the soot from coal fires blackened every surface; parks, libraries, museums, and other public spaces were rare, and largely shut off to the masses; and every street was covered in horse manure and the flies it attracted.

Planners of the time began to react against the unhealthy, miserable conditions, and proclaimed that cities, themselves, were the problem. So they began to design un-city-like, even anti-city, communities. The first, and most revolutionary, of these planners was the Englishman Ebenezer Howard, who began the Garden City movement. The Garden City was to be a community of 30,000 people or less, where the working class could live and work while still being in proximity to nature (or at least greenery). As the name suggests, gardens would be the most prominent feature of the city, with housing, shops, factories, and the like each segregated within its own district. The design was prescribed and geometrical, like a formal English garden, with no errant petunias sticking up in the rose bed. Linking it all together would be sweeping drives, like lovely, curving garden walks.

"Letchworth Garden City" from Principles of City Planning (1931) by Karl Baptiste Lohmann (click to enlarge)

A couple of actual Garden Cities, Letchworth and Welwyn, were subsequently built in England, more or less according to Howard’s plan. In the US, Clarence Stein designed Radburn, NJ after Garden City principles. However, the much greater impact was on the thinking of architects and planners, who embraced the concept wholeheartedly. One of these was the influential Frenchman le Corbusier, who kept the ideas of greenery and strict separation of uses, but replaced the relatively low buildings in Howard’s conception with skyscrapers. In The Urban Prospect, Lewis Mumford described le Corbusier’s design as bringing together “the machine-made environment, standardized, bureaucratized…; and to offset this, the natural environment, treated as so much visual open space….” Le Corbusier also enthusiastically associated the plan with its natural transportation mode, the automobile, which when he was writing in the 1920s was already becoming the mode of choice in much of the Western world. This plan he called Radiant City.

Finally, at about the same time the City Beautiful movement was popular. This movement promoted the construction of monuments and civic centers (Denver’s being a prime example), again on the same general model of isolated buildings carefully placed to stud large lawns, all set well back from the road.

All three movements were vehement reactions against the traditional urban building pattern. Jacobs lumps them together, disparagingly calling them Radiant Garden City Beautiful, and blames them for many of the planning ills of her day, while marveling at their influence on planning thought. Indeed, clear marks of Modernist ideas are visible today in Boulder. The Flatiron Industrial Park, with its large, monolithic buildings set amongst perfectly manicured lawns, all surrounded by wide, gently arcing roadways, is a direct conceptual descendant of this tradition. The complex containing Boulder’s Municipal Building and main library owes allegiance to the City Beautiful movement. Even Northfield Village, currently under construction at the corner of 57th Street and Jay Road, can trace its high surrounding fence, its inward-looking demeanor with few connections onto the main streets, and its monoculture of residential use to Garden City ideas. It is truly remarkable that in Boulder in 2011, we are still designing the city in reaction to conditions in 19th-century London.

As a reader, it’s also important to understand the context in which Jacobs was writing. The word order in her title was not accidental. In 1961, the death, or at least continued decay, of many big American cities seemed inevitable. Crime rates were high, downtowns were crumbling, businesses and the middle class were moving to the suburbs in droves. “Death” was on its way, and “Life” may have seemed wishful thinking. Today many American cities are much more vital: a glance at Denver’s LoDo or New York City’s declining crime rates confirms that.

Like its title, The Death and Life of Great American Cities is wide-ranging and often verbose. Jacobs addresses the virtues of sidewalks, the uses and misuses of parks, the economics of urban investment, subsidized housing, and more. She rails with particular vehemence against housing projects, which she viewed as more or less Garden City for poor people. It’s perhaps in large part thanks to Jacobs that housing projects are now almost universally recognized as an abject failure.

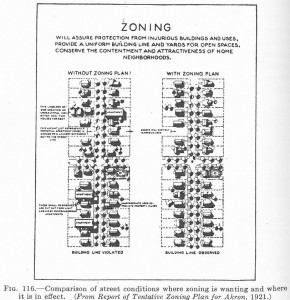

Jacobs’ antipathy toward highly prescriptive, rigid planning schemes that strictly separate uses, including her critique of Euclidean zoning, made her something of a darling among libertarians. There’s nothing to indicate that her views were dictated by any larger ideology or agenda, though. She opposed Modernist separation of uses from a pragmatic standpoint, because it was detrimental to the city and the people and activities that comprise it. Jacobs surely would not have taken kindly to Boulder’s zoning code, which, while something of a hybrid, for the most part enforces just the kind of strict separation of uses that she criticizes.

Her prescription for how to fix projects — meaning mainly housing projects but applying to any Garden City-style development — is particularly interesting from a current perspective. She suggests many of the same tools that planners today use, including those in Boulder: re-establishing the street grid through the development, for instance, and introducing buildings that line and address the streets. These approaches can be seen in the (by no means fully successful) transformation of the Crossroads Mall into Twenty Ninth Street.

But the heart of the book, as Jacobs herself points out, is in her formulation of “generators of diversity.” This is before “diversity,” in the senses of race, ethnicity, gender, and so on became a buzzword. Jacobs says she means diversity of use, a very fine-grained mix of all the kinds of activities — economic activities, social activities, recreational activities, and more — that go on in a city. But a better term today might be dynamism: the level of healthy activity in a city. This diversity, or dynamism, she contrasts with what she calls The Great Blight of Dullness.

Her four factors creating diversity of use in a neighborhood are:

- A fine-grained mix of primary activities, meaning those that someone would travel across the city to engage in. Besides housing and employment, primary activities include destination shopping, premier arts facilities, government offices, main libraries, parks that draw from across the city, destination restaurants and bars, etc.

- Short blocks in the street grid.

- Buildings of a wide range of ages and conditions. The idea is to have a wide range of rent or purchase costs, to provide spaces for established, successful firms that can afford nice digs, as well as spaces for enterprises that are just getting going, or perhaps (as in artists’ studios) may not be highly profitable.

- A sufficient density of people, who may be residents or people there because of other primary uses.

All four of these conditions are directly contrary to Modernist planning. Most suburban neighborhoods are residential-only, with relatively large blocks, houses of very similar vintage, and very low density. Flatiron Industrial Park has almost exclusively office and industrial uses, very long “blocks,” buildings that almost uniformly date from the 1980s, and low average density.

Jacobs spends a good deal of ink discussing the four conditions, which she claims are both necessary and sufficient for creating diversity of use. That might be going too far, but they all clearly contribute to diversity and thus warrant more consideration in urban design. Other than in the residential realm, the value of a mix of more- and less-expensive buildings in an area, as called for in condition 3, gets particularly little attention from planners.

But what’s especially relevant today about Jacobs’ conditions is that numbers 1, 2, and 4 are all widely accepted as means of making a neighborhood less car-dependent: mixed use allows for the possibility to walk among home, shopping, and work; a fine-grained street grid means shorter distance around blocks and a more pedestrian-scale feel, and a more diffuse distribution of auto traffic; and density means more activity within a given walking distance, making walking and transit more viable alternatives to the automobile.

The question of car-oriented design is something Jacobs touches on only lightly. She saw the degrading effects of the automobile on a city, but for her the greater evil was Garden City-style development, with the car just a mechanism that allows that style to be viable. But she was writing before the days of ozone alerts, oil wars, global warming, and the obesity epidemic. Today, to address these and other ills that 50-plus years of auto-centric development have helped bring about, planners are turning from designing the urban form for cars, almost invariably using Modernist-inspired motifs, to designing for people (and their mobile form, pedestrians) using models that predate Modernist ideas. New Urbanism, in particular, hearkens back to the urban form of the very cities that so disturbed Howard and the others — though, it’s hoped, minus the turn-of-the-century evils.

So what Jacobs tells us is that pedestrian-oriented design is also good for the dynamism of the city: its economic vigor, its social strength, the safety of its streets, and so on. Traditional urban design with its mix of land uses, short, walkable blocks, and relatively high density produces a happy convergence of these traits. But that should come as no surprise. It was the standard urban model around the world for thousands of years prior to the fossil fuel age, until Modernist ideas, made practical by the popularity of the automobile, supplanted it.

The underlying theme and motivating force behind all of Jacobs’ urban planning guidelines is her emphasis on community. She wants readers to see the city as comprised of people and their activities, not buildings and streets and marks on a map. Buildings and streets and maps are important, to be sure, but they’re not the point. They’re simply the means that allow people to congregate in the city and engage in the myriad activities that give cities their unique vitality. The Death and Life of Great American Cities could well instead be titled Cities for People, as is a recent book by the architect and planner Jan Gehl. Ebenezer Howard clearly had people at heart when designing his Garden Cities, but subsequent planners adopted the form and abandoned the objective. (Geddes Smith titled a 1930 article about Radburn, “A Town for the Motor Age.” How different from Cities for People!) Reading Jacobs today, we see that sadly, the last fifty years have not erased the need to remind designers that people — not developers’ profits, not cars, not architects’ egos — should be the point.

The enduring, or perhaps resurgent, value of Jacobs’ book lies in the case it makes for a traditional urban form that, today, is widely recognized as a model that planners must return to in order to redress decades’ worth of Radiant Garden City Beautiful design. The book endures as a passionate, articulate, approachable defense of urbanism as an alternative to The Great Blight of Dullness wrought by Modernism — a planning model that remains remarkably pervasive, even in Boulder.

Thanks to Louis Krupp for his extensive contributions to the author’s urban planning library.

(7 votes, average: 4.86 out of 5)

(7 votes, average: 4.86 out of 5)