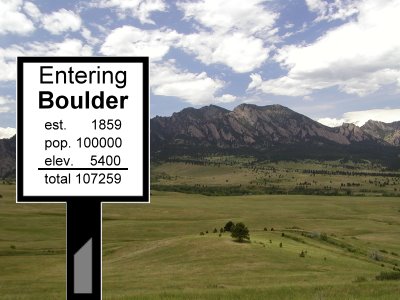

After 150 years, the population of the City of Boulder has finally surpassed one hundred thousand, according to a recent estimate by the U. S. Census Bureau. The report indicated that the city’s growth rate since 2000 was 6 percent, well below the rates experienced by the State of Colorado and the nation as a whole. That’s not exactly evidence of Boulder as a boomtown.

Growth is a topic of frequent debate and discussion in Boulder. However, the spectre of rapid growth is trumped by the reality that the city is growing at only a slow and steady pace. In fact, the city’s growth rate between 2000 and 2009 was about half the rate experienced in the previous decade. Boulder’s population boom years were from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s. Things have slowed considerably since then.

Several factors have combined to reduce the city’s population growth rate—stricter development controls and the physical boundary created by the open space system—and have limited the kind of sprawl and speculative development that has afflicted many other cities. Yet the slowdown in population growth did not adversely affect the city’s economy. Even during the “Great Recession” of the past two years, Boulder experienced far fewer residential foreclosures, a lower unemployment rate, and fewer job losses than many cities of comparable size. Retail sales are rebounding, and new businesses are opening.

In fact, the health of Boulder’s economy creates some issues when it comes to population growth. Boulder clearly is a popular destination. The city is regularly featured on “best of” lists sponsored by magazines, research organizations, universities, and the like. And while many of those lists are pure hype, there is evidence that people who urbanist Richard Florida calls “the creative class” are attracted by Boulder’s environment, progressive attitudes, available jobs, and green reputation.

Boulder has a balanced economic base characterized by higher education, the research labs, outdoor recreation, organic foods, emerging “green tech” businesses, and local service and retail firms. As that economic base creates more jobs those employees have to live somewhere. So, we’re back to the jobs/population imbalance that occupied public attention a few years ago.

Since the city’s population growth rate is slow and steady, it appears that many of the newcomers live nearby and commute to jobs in Boulder. Housing prices are lower in places such as Lafayette and Superior, but the drive to Boulder for work or to enjoy the city’s restaurants, shops, and open space is fairly short. To someone moving here from Atlanta, Dallas, or San Diego, the commute time is, by comparison, minimal. But those car commutes create pollution and consume gasoline. They also clog many of Boulder’s thoroughfares during rush hours.

There is also a demand for housing within the city of Boulder. Between 2000 and 2009, the City of Boulder issued building permits for an average of about three hundred new residential units per year, most of which were condominiums and apartments. If the city’s growth rate of 6 percent continues during the decade of 2010 to 2020, we’ll need to add another three thousand to four thousand units. Where will we put them? Stopping all development is unrealistic, and we can’t put up gates to keep people out.

For many Boulderites, “density” is as much a dirty word as “growth.” The boogeyman here is exemplified by tall condominiums (four stories is tall?) like those lining Canyon Boulevard downtown. But changing demographics (more young people, fewer children, and more elderly residents) means that the mix of housing developed in Boulder will continue to be weighted heavily to multifamily buildings.

The best place for density is downtown and along the major corridors that already have ample public transit, such as Broadway, 30th Street, Valmont Road, and Table Mesa Drive. The “transit village” in east Boulder, though burdened by a mediocre and unimaginative area plan, is another suitable location for higher-density housing. In many cities, older shopping centers are being redeveloped into a pedestrian-friendly design that blends housing with retail space. That’s likely to occur in Boulder. Diagonal Plaza at 28th Street and Iris Avenue is a prime example of where such development could occur.

We’ll also need to capitalize on our city’s policy of balanced transportation systems as “peak oil” makes gasoline for cars more expensive. Boulder is fortunately ahead of the game here, with a good bus system, bike lanes and paths, and sidewalks. Some of the commuting pressure may be alleviated by plans for bus rapid transit lanes on U.S. 36 and ultimately commuter rail.

So, what’s ahead for Boulder between now and 2020? It’s hazardous to one’s professional reputation to make too many projections based on past performance. For example, in 2000, Las Vegas and Phoenix were two of the most active housing markets in the country. Today those markets are in the toilet. Situations change.

But unless things really fall apart, Boulder has an opportunity to do quite well as we capitalize on our strengths. That means we need to do the following:

- Not get too obsessed about growth. Boulder enjoys slow-but-steady population growth, which is not likely to return to the boom times of forty years ago.

- Carefully accommodate and manage growth where it best fits. Conversely, there’s no need for local government to encourage growth such as the City of Boulder does today with an unnecessary “economic vitality” incentives and subsidies program.

- Conduct long-term planning by considering the city’s “carrying capacity.” In other words, we need to assess how many people can ultimately be served by our water supplies. Are we willing to allow increased congestion to clog intersections? What’s the capacity of our sewage treatment system? Unfortunately, our planners and elected officials have refused to consider thoroughly those underlying issues, and it’s time to do so as we update the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan this year.

- Continue to stress quality of life for all people. It’s better to spend the funds allocated for business incentives on libraries, parks, open space, transportation, and public safety instead of on growth generation.

- Consider our form of municipal government. Does the archaic city manager form of government best serve an increasingly diverse city of more than one hundred thousand? Should we look at electing at least some of our City Council members by district? Should the people, instead of the City Council, elect the mayor?

- Plan now to address the effects of climate change and peak oil on Boulder, including transportation, energy, water, and agriculture. Climate change and peak oil are two converging problems that are being thoroughly ignored by some “leaders” in Washington.

Perfection is not attainable, but Boulder is well positioned to make the most of the opportunities that will arise. We’ll have to be equally shrewd to address the new problems that will pop up, too. Excessive population growth is not one of them.

Boulder Tops the Century Mark

By Eric Karnes

After 150 years, the population of the City of Boulder has finally surpassed one hundred thousand, according to a recent estimate by the U. S. Census Bureau. The report indicated that the city’s growth rate since 2000 was 6 percent, well below the rates experienced by the State of Colorado and the nation as a whole. That’s not exactly evidence of Boulder as a boomtown.

Growth is a topic of frequent debate and discussion in Boulder. However, the spectre of rapid growth is trumped by the reality that the city is growing at only a slow and steady pace. In fact, the city’s growth rate between 2000 and 2009 was about half the rate experienced in the previous decade. Boulder’s population boom years were from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s. Things have slowed considerably since then.

Several factors have combined to reduce the city’s population growth rate—stricter development controls and the physical boundary created by the open space system—and have limited the kind of sprawl and speculative development that has afflicted many other cities. Yet the slowdown in population growth did not adversely affect the city’s economy. Even during the recent “Great Recession” of the past two years, Boulder experienced far fewer residential foreclosures, a lower unemployment rate, and fewer job losses than many cities of comparable size. Retail sales are rebounding, and new businesses are opening.

In fact, the health of Boulder’s economy creates some issues when it comes to population growth. Boulder clearly is a popular destination. The city is regularly featured on “best of” lists sponsored by magazines, research organizations, universities, and the like. And while many of those lists are pure hype, there is evidence that people who urbanist Richard Florida calls “the creative class” are attracted by Boulder’s environment, progressive attitudes, available jobs, and green reputation.

Boulder has a balanced economic base characterized by higher education, the research labs, outdoor recreation, organic foods, emerging “green tech” businesses, and local service and retail firms. As that economic base creates more jobs those employees have to live somewhere. So, we’re back to the jobs/population imbalance that occupied public attention a few years ago.

Since the city’s population growth rate is slow and steady, it appears that many of the newcomers live nearby and commute to jobs in Boulder. Housing prices are lower in places such as Lafayette and Superior, but the drive to Boulder for work or to enjoy the city’s restaurants, shops, and open space is fairly short. To someone moving here from Atlanta, Dallas, or San Diego, the commute time is, by comparison, minimal. But those car commutes create pollution and consume gasoline. They also clog many of Boulder’s thoroughfares during rush hours.

There is also a demand for housing within the city of Boulder. Between 2000 and 2009, the City of Boulder issued building permits for an average of about three hundred new residential units per year, most of which were condominiums and apartments. If the city’s growth rate of 6 percent continues during the decade of 2010 to 2020, we’ll need to add another three thousand to four thousand units. Where will we put them? Stopping all development is unrealistic, and we can’t put up gates to keep people out.

For many Boulderites, “density” is as much a dirty word as “growth.” The boogeyman here is exemplified by tall condominiums (four stories is tall?) like those lining Canyon Boulevard downtown. But changing demographics (more young people, fewer children, and more elderly residents) means that the mix of housing developed in Boulder will continue to be weighted heavily to multifamily buildings.

The best place for density is downtown and along the major corridors that already have ample public transit, such as Broadway, 30th Street, Valmont Road, and Table Mesa Drive. The “transit village” in east Boulder, though burdened by a mediocre and unimaginative area plan, is another suitable location for higher-density housing. In many cities, older shopping centers are being redeveloped into a pedestrian-friendly design that blends housing with retail space. That’s likely to occur in Boulder. Diagonal Plaza at 28th Street and Iris Avenue is a prime example of where such development could occur.

We’ll also need to capitalize on our city’s policy of balanced transportation systems as “peak oil” makes gasoline for cars more expensive. Boulder is fortunately ahead of the game here, with a good bus system, bike lanes and paths, and sidewalks. Some of the commuting pressure may be alleviated by plans for bus rapid transit lanes on U.S. 36 and ultimately commuter rail.

So, what’s ahead for Boulder between now and 2020? It’s hazardous to one’s professional reputation to make too many projections based on past performance. For example, in 2000, Las Vegas and Phoenix were two of the most active housing markets in the country. Today those markets are in the toilet. Situations change.

But unless things really fall apart, Boulder has an opportunity to do quite well as we capitalize on our strengths. That means we need to do the following:

• Not get too obsessed about growth. Boulder enjoys slow-but-steady population growth, which is not likely to return to the boom times of forty years ago.

• Carefully accommodate and manage growth where it best fits. Conversely, there’s no need for local government to encourage growth such as Boulder’s does today with an unnecessary “economic vitality” incentives and subsidies program.

• Conduct long-term planning by considering the city’s “carrying capacity.” In other words, we need to assess how many people can ultimately be served by our water supplies? Are we willing to allow increased congestion to clog intersections? What’s the capacity of our sewage treatment system? Unfortunately, our planners and elected officials have refused to consider thoroughly those underlying issues, and it’s time to do so as we update the Boulder Valley Comprehensive Plan this year.

• Continue to stress quality of life for all people. It’s better to spend the funds allocated for business incentives on libraries, parks, open space, transportation, and public safety instead of on growth generation.

• Consider our form of municipal government. Does the archaic city manager form of government best serve an increasingly diverse city of more than one hundred thousand? Should we look at electing at least some of our City Council members by district? Should the people, instead of the City Council, elect the mayor?

• Plan now to address the effects of climate change and peak oil on Boulder, including transportation, energy, water, and agriculture. Climate change and oil are two converging problems that are being thoroughly ignored by some “leaders” in Washington.

Perfection is not attainable, but Boulder is well positioned to make the most of the opportunities that will arise. We’ll have to be equally shrewd to address the new problems that will pop up, too. Excessive population growth is not one of them.