Editor’s note: Throughout the summer we will run a serialized version of PLAN-Boulder County’s A Transportation Vision for Boulder. This is part 3 of section 1. To read the entire paper, start with the Introduction.

Congestion, continued

Yogi Berra, the iconic Yankee catcher and manager, once summed up the congestion paradox when he said the place became so crowded that no one wanted to go there anymore.

We all know that an attractive city—particularly its town centers—will draw people. In healthier, more pleasant cities, the number of people drawn to a town center leads to an ambiance that is more festive, convivial, and enjoyable. Humans tend to be sociable by nature, which means that many seek out places that entice a gathering of people. A place to see and be seen. A place where we can expect to serendipitously bump into friends as we walk on a sidewalk or square. A place where we can share the news of the day and linger with our fellow residents. Or share a laugh or an idea. A place that at times creates a collective effervescence of people enjoying experiences with others. A place, in other words, that is likely to be collectively rewarding. The Pearl Street pedestrian mall and surrounding downtown area in Boulder has achieved healthy town center status.

Indeed, the prime reason for the creation of cities throughout history is to promote such exchange. Exchanging goods, services, synergistic ideas, and neighborliness with others is the lifeblood of a thriving city.

For these reasons, an important sign of a healthy town center is that it is a celebrated, beloved place that regularly draws and gathers many citizens of the community. Unhealthy communities, by contrast, are featured, in part, by citizens who are more isolated and more alone. Sociologists such as Robert Putnam would say that these loner cities have low social capital.[1]

A convenient, convivial town center with a cozy, compact spacing of people, housing, retail, and cars is desirable and should be normal. It is a clear sign that a city is attractive and in good health.

Dave Mohney once said that the most important task of the urbanist is to control size. This point is crucial. Healthy town centers must retain a compact, human scale. Trying to reduce congestion in a town center is one of the most toxic things that can be done to a town center, as the main objective of congestion reduction is to substantially increase sizes and spaces from a human scale to a car scale with huge roads, huge intersections, and huge parking lots. The enormity of these huge, deadening car spaces sucks the lifeblood out of a town center.[2]

Striving to reduce congestion in the Boulder town center and other emerging town centers is to work at cross purposes to what we seek and should expect and celebrate as part of a strong, vigorous city. Widening roads and intersections to smooth traffic flow (or reduce congestion) is akin to the measures taken by many engineers in the past who fervently believed that it was necessary to convert streams into concrete channels in order to control water flow and reduce flooding. Today, we recognize that doing so destroyed the stream ecosystem and made flooding worse downstream. It is time for us to realize that at least in town centers, widening roads and intersections will destroy the human ecosystem and make congestion worse.

The State of California is starting to recognize the counterproductive nature of fighting to reduce congestion at least with regard to the provision of some of its plans for bicycling infrastructure, and is looking at adopting alternatives that Boulder should also consider: for example, controlling such things as total vehicle miles traveled (VMT), total fuel consumption, or car trip generation. California is also looking at assessing and promoting multi-modal level of service (LOS), and adopting the position that infill development improves overall accessibility. City of Boulder staff in 2014 added neighborhood access and vehicle miles traveled per capita to the list of Transportation Master Plan objectives, and is starting to evaluate use of a multi-model LOS standard.[3]

Another emerging service metric is the “Person LOS” standard. A Person LOS prioritizes the number of people that pass through an intersection, rather than the number of vehicles. By doing so, a Person LOS gives the highest intersection design priority to transit and the lowest priority to single-occupant vehicles. This metric is being strongly considered for adoption by the Denver Regional Council of Governments and is already being used in cities such as Portland, Oregon.

Yet another approach that has been used is to keep the automobile congestion objective, but create an exception for a town center, because fighting against congestion in a compact, walkable community location is almost entirely inappropriate and counterproductive to the needs of a healthy town center. Florida provides an instructive example of calling for exceptions.

In 1985, Florida adopted a growth management concurrency (or adequate facilities) law that prohibited development that reduced level of service standards adopted by the community for such things as parks, potable water, schools, and road capacity. The law seemed highly beneficial when enacted, for obvious reasons. It was also an important tenet of the law that to fight sprawl and promote community objectives, in-town development should be encouraged, and remote, sprawling development should be discouraged. But many soon realized that there was a significant unintended consequence with the growth management law. The concurrency law, when applied to roads, was strongly discouraging in-town development and strongly encouraging sprawl development.

Why? Because available road capacity tends to be extremely scarce in town centers, and much more available in sprawling, peripheral locations. Concurrency therefore made sprawl development much less costly and infill development much more costly. The opposite of what the growth management law was seeking.

The solution was to allow communities to adopt what are called exception areas in the city. That is, cities were authorized to designate various in-town locations where the city sought to encourage new development as transportation exception areas that would not need to abide by concurrency rules for road (or intersection) capacity when a new, in-town development was proposed.

When the State of Florida decided to allow transportation exception areas, it was specified that such exception areas would only be allowed if certain design, facility and service conditions were in place. To adopt transportation exception areas, the community had to show that it was also providing a full range of travel choices—choices that were available for those who wished to find alternatives to driving in more congested conditions.

Air Emissions

One of the most important consequences of designing for free-flowing traffic, counterintuitively, is the high levels of air emissions that result.

It is commonly believed that if we reduce traffic congestion by, say, widening roads or synchronizing traffic signals, we will reduce air pollution and gasoline consumption.

Isn’t this obviously true? After all, don’t such measures that smooth traffic flow and reduce stop-and-go traffic improve fuel efficiency and reduce air emissions?

Environmentalists continue to oppose road widening because it will promote sprawl, but grudgingly end up admitting to themselves, when push comes to shove, that road widening or turn lanes will reduce air pollution and gas consumption. Widening a road is not all bad, according to this view.

As a result, the homebuilding and road widening lobbies have regularly been successful in their efforts to gain political support for widening roads. Most environmentalists, interest groups, and elected officials believe that we need to expand roads and intersections and parking to reduce gas consumption and air emissions.

The stop and go problem is correct, except for one thing: it applies only to individual cars. When we apply eased car travel to an entire community of drivers (in a community where roads and parking are free to use), we find that many new car trips are induced, as discussed previously. The extra trips would not have occurred had the car travel and parking not been so easy and cheap.

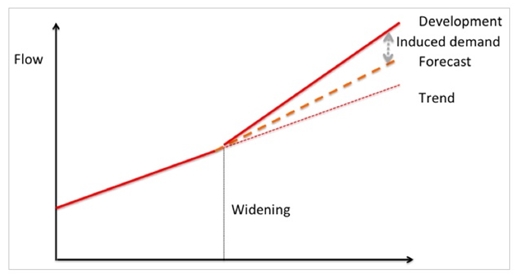

Eric Jaffe, in CityLab, describes induced demand by using a chart. He notes that the chart “ illustrates the phenomenon of induced demand [created by Anthony Downs ‘Triple Convergence’ dilemma]. The red line represents vehicle flow along a given road. Traffic steadily rises until someone decides the road [or intersection] needs to be widened. Then the original trend line (dotted red) gets replaced with an even greater travel forecast (dotted orange), as we’d expect by creating more road capacity. But the actual new level of travel developed by this widening (solid red) is even greater than the forecast predicted.”[4]

In a ground-breaking worldwide study of cities in 1989 (Cities and Automobile Dependence), Jeffrey Kenworthy and Peter Newman came to a startling, counterintuitive conclusion: cities that did not spend enormous amounts of money to widen roads and ease traffic flow showed lower levels of air emissions and gas consumption than cities which went on a road-widening, ease-of-traffic-flow binge. This was true even though those communities that did not spend large amounts on widening often had high levels of congestion.

The reason is that nearly all roads and parking spaces are free to use. There is almost never a need to pay a toll to drive on a road, or pay a parking meter. Free-to-use roads and parking inevitably encourage low-value car trips. That is, trips that are of relatively low importance, such as a drive across town on a major road during rush hour to walk the dog or buy a cup of coffee.

The most effective way to reduce low-value car trips is to charge motorists for using the road or parking space. Toll roads and priced parking are very equitable user fees. The more you use a road or parking space, the more you pay. In doing so, motorists are more likely to use the road or parking space only for the most important car trips (that is, more efficiently), such as the drive to or from work, or medical emergencies, for example.

When roads and parking spaces are free to use, however, they become congested quite quickly because of all the “low-value” car trips on the road. Unfortunately, it is very difficult, politically, to charge motorists for using a road or a parking space. The result is that almost no road or parking space is tolled or priced.

On the other hand, a consequence of moderate levels of cars crowding a street is that a great many motorists decide in both the short and long term to do something else. They opt to use a more free-flowing road. They use transit, walk, or bicycle. They travel at non-rush hour times, or pay a toll to use a managed lane. In the long run, many will move to a location that is closer to their daily destinations as a way to avoid the slower road. And as Kenworthy and Newman found in their worldwide study of cities,[5] this means that cities with slower car travel see less air pollution and less gas consumption because so many low-value car trips have been eliminated by the car crowding.

In existing and emerging town centers, slower car travel, smaller street and parking lot sizes, and fairly administered pricing of roads and parking maximizes travel choice and transportation efficiency. These strategies minimize excessive car dependence and low-value car travel. They maximize the efficiency of street and parking lot use. All forms of travel therefore benefit—pedestrians, transit users, bicyclists, as well as motorists—and air emissions are minimized.

Continue to the section: Urban Design

[1] Putnam, Robert D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. Simon and Schuster.

[2] As was said in Vietnam, excessive road sizes, intersections and parking lots kill a town center in the name of saving it.

[3] A standard that goes beyond the conventional approach of only assessing the quality of travel by a motorist, but also the quality for pedestrians, bicyclists and transit users.

The mission of PLAN-Boulder County is to ensure environmental sustainability, promote far-sighted, innovative, and sustainable land use and growth patterns, preserve the area’s unique character and desirability, and reduce our carbon footprint and environmental impact.

PLAN-Boulder County envisions Boulder County as mostly rural with open land between cities and towns that support working farms on good agricultural land and provides for conservation of critical habitats for wildlife and native flora. Within Boulder and neighboring communities, urban boundaries limit sprawl and growth is directed to meet community goals of housing affordability, diversity of all kinds, environmental sustainability, neighborhood identity, and a high quality of life. PLAN-Boulder County further supports green building practices that minimize energy use and greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, PLAN-Boulder County supports a more balanced transportation system that actively promotes public transit, bicycle commuting, and pedestrian travel, and provides for smarter use of automobiles.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the various city and county organizations with which the authors are affiliated.

Dom Nozzi, principal author of this paper, is a member of the PLAN-Boulder County Board of Directors and the City of Boulder Transportation Advisory Board. Mr. Nozzi has a BA in environmental science from SUNY Plattsburgh and a Master’s in town planning from Florida State Univ. For 20 years, he was a senior planner for Gainesville, Forida and was also a growth rate control planner for Boulder. He has authored several land development regulations for Gainesville, has given over 90 transportation speeches nationwide, and has had several transportation essays published in newspapers and magazines. His books include Road to Ruin and The Car is the Enemy of the City. He is a certified Complete Streets Instructor providing Complete Streets instruction throughout the nation.

Pat Shanks, Jeff McWhirter, Alan Boles and Scott McCarey also contributed to this paper.